Every time I leave New York and land back in Europe or in Asia, I can immediately tell which apps have a global presence and which apps only deploy to a single US region. Everything just immediately feels a little slower. The pull to refresh feels a bit sluggish, the preview images take a little longer to load, and even native apps just feel less responsive.

Floored Latency

The speed of the experience you can offer your users is floored by a few variables, most notably the physical distance from the origin server to where the user is actually sitting.

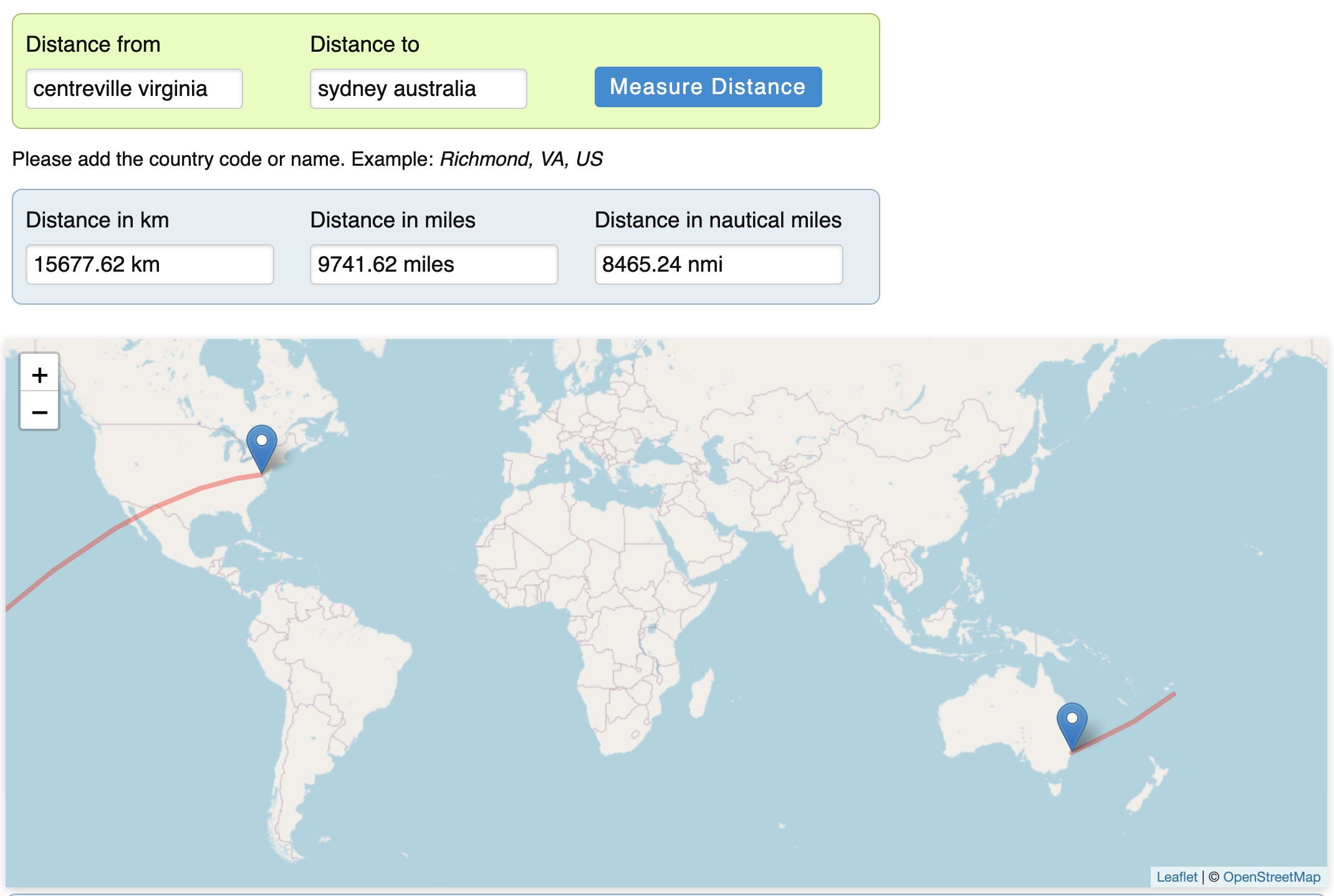

Us-east-1 (appropriately located right by "Centreville, Virginia") is one of the main data centers run by AWS. If you're a startup (or even quite a few mature companies), you are likely to deploy your application here. If you manage a stateful service, or your architecture doesn't support distributed compute, you are likely to only deploy here. If you have users in Sydney, Australia, any network request you make will need to travel 15,677km to make it there, as the crow flies.

Distance from Centreville, Virginia to Sydney, Australia

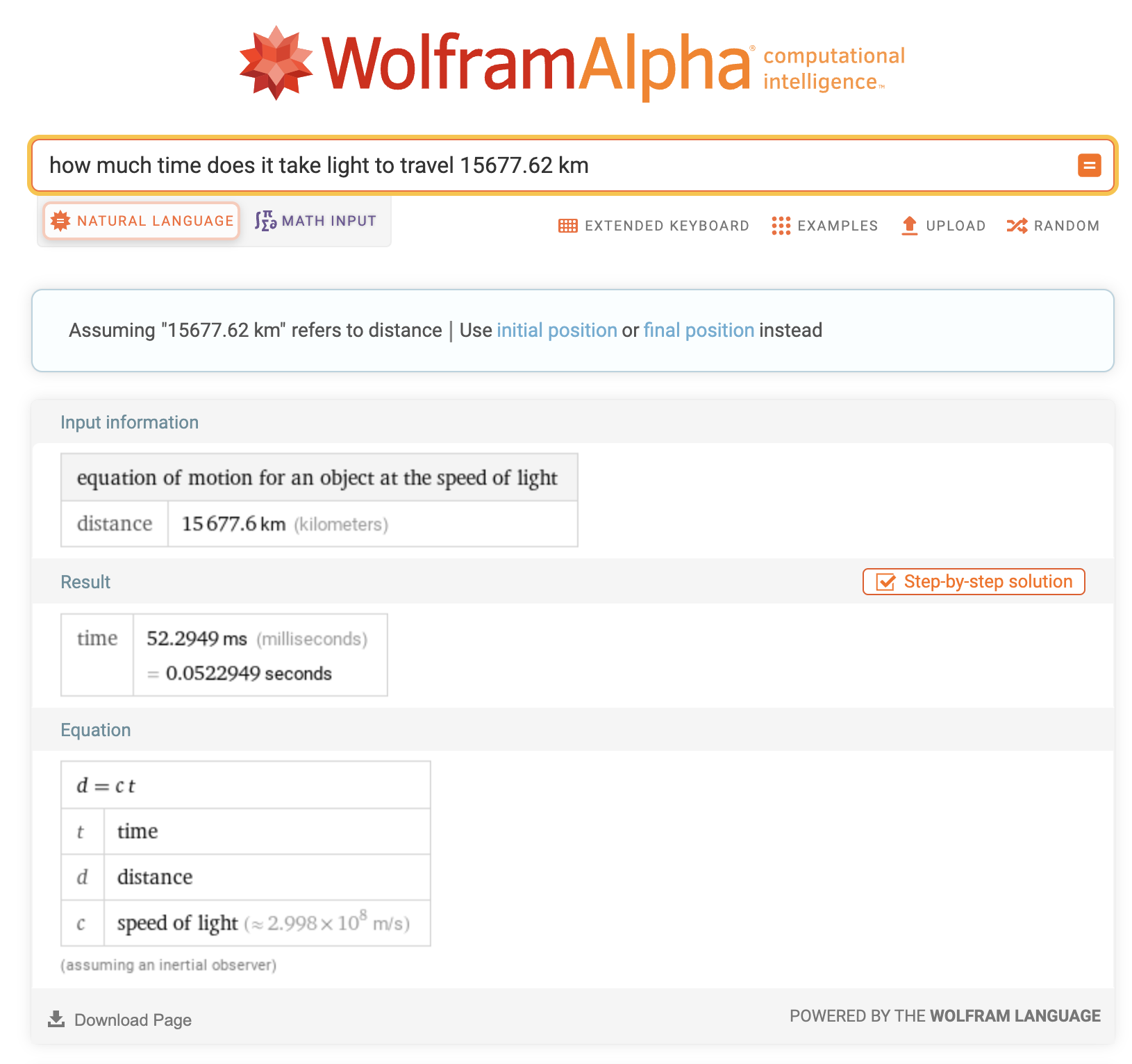

If you're traveling at:

-

The speed of light

-

as the crow flies

-

with no overhead

then that means that you are floored at 104ms of latency for your request.

Time in takes for the speed of light to travel from us-east-1 to Sydney

And this is assuming no interference, other traffic, or time spent handling the request.

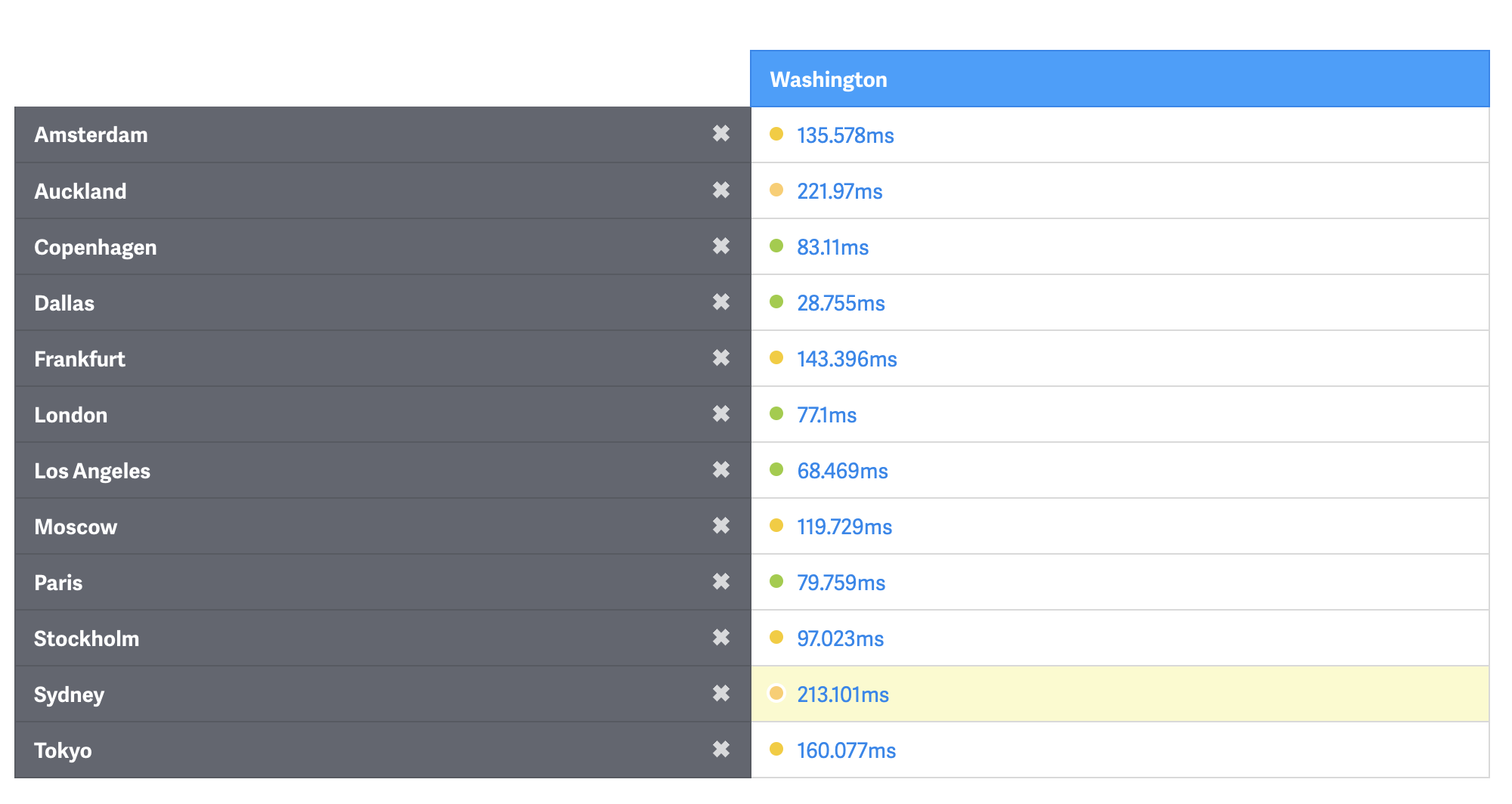

In reality, the ping you'll experience will be worse, at around 215ms (which is a pretty amazing feat in and of itself - all those factors above only double the time it takes to get from Sydney to the eastern US).

Ping to various cities around the globe

And this is just what is added on top of everything else that happens on a request - TLS termination and DNS lookup. This isn't a one-time hit to performance - every connection the client opens needs to go through TLS termination, or be queued up on the same connection and be executed serially. For simple sites that are basic html and css this isn't an issue, but for many sites you'll have dozens of requests to different domains, and each one will need to be established and terminated.

Compounding latency

The full TLS 1.2 handshake requires 2 round-trips to complete, and when combined with TCP's SYN and SYN-ACK negotiation it extends to 3 full round-trips. While, TLS 1.3 reduces that to two round-trips when under TCP, it still adds considerable latency to every connection. 1

The problem gets compounded when you realize many requests are chained, or dependent on each other. Images in CSS files can only be requested once the CSS has been downloaded, and the CSS can only be downloaded once the browser has parsed the HTML. HTTP/2 and its multiplexing improves this but doesn't completely solve this - each of these could be hosted on a different domain, or saturate the max concurrent connections from your browser.

Protocol improvements also don't fix fundamental issues with how the site is architected - if you have an SPA that hasn't been optimized properly, your browser needs to first download all the content, then execute the javascript, and only once the JS has executed will it begin to make the API requests and fetch the assets to populate the content of the page.

It's cascading latency hell. In aggregate this can add thousands of milliseconds for a simple site.

Realized latency

Having spent so much time trying to optimize web pages and API responses for performance, I've gotten a pretty good internal model for latency. I can't quite tell the difference between a us-east-1 server when I'm in New York versus San Francisco, but I can definitely tell if you've got an instance deployed in eu-central-1 or not when I'm in Italy, or ap-east-1 when I'm in Sydney. It's much easier to tell with native apps, where the UI is much more responsive and the only variable is the duration of the API request. You'll pull to refresh on a list and it'll hang for just a little longer than you're used to.

Using a global CDN can help get your assets to your users quicker, and most companies by this point are using something like Cloudflare or Vercel, but many still only serve static or cached content this way. Very frequently the origin server will still be a centralized monolith deployed in only one location, or there will only be a single database cluster.

As soon as you land back in the United States and turn of Airplane mode on your phone everything just starts feeling... snappier? A little more fluid? As much as T-Mobile and Verizon would like to take credit for that I don't think theres much more to it than the physical location of the servers and where you are at that moment.