Interesting Snippets

A collection of short ideas, anecdotes, and excerpts that I found interesting. I did not write any of the following, and attempt to give attribution where possible.

I do not necessarily agree with the views - they simply succintly and clearly say what I believe to be an interesting topic or insight.

On Planned Obsolesence

From u/Awesomebox5000 on a thread on planned lifecycles

Planned obsolescence doesn't really exist in the way most people think it exists. Manufacturing processes have matured to the point that we can design a product where the average unit will last at least a certain period of time with the estimates on "at least" getting better all the time. People keep demanding products to be cheaper and cheaper so companies build less and less durability in the products. They're designed to last at least a certain period of time, not self-destruct after a certain period of time; it's actually REALLY HARD to make something purposefully fail at the exact moment you want it to without being obviously designed to fail.

Basically, it used to be that we had to overbuild the shit out of everything in order to ensure that it would work at all; this led to a lot of products that were needlessly expensive. Take a blender for example, the first price point I could find for a household blender was from 1937 at a price of $29.75. Adjusted for inflation, that's over $500 today; which also happens to be around the price point you need to get a brand new blender that will last for decades. You don't have to spend that much money on a blender because there are much cheaper options available that aren't designed to last as long but the cheaper blenders aren't designed to fail, they're designed to be less expensive which, necessarily, reduces the average lifespan of the product.

There are totally a few classic planned obsolescence examples out there; but the majority of the time people are just expecting their walmart blender to last as long as a Blendtec. Most of what people feel is planned obsolescence can really be explained by the Terry Pratchett quote about boots:

The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money. Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of OK for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars. Those were the kind of boots Vimes always bought, and wore until the soles were so thin that he could tell where he was in Ankh-Morpork on a foggy night by the feel of the cobbles. But the thing was that good boots lasted for years and years. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that'd still be keeping his feet dry in ten years' time, while the poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet. This was the Captain Samuel Vimes 'Boots' theory of socioeconomic unfairness.

On Modern Political Thought

From u/TheVetSarge on a thread after the 2016 Presidential Election

In the midst of all the crying and hand-wringing about racists, people seem to have forgotten that there are people who will always vote Republican because Republicans back the things they think are important, just like there are people who will always vote Democrat because they think Democrats back the things they think are important.

The majority of racists probably voted for Donald Trump. This doesn't mean the majority of people who voted for Donald Trump are racists. They voted for Donald Trump not because he was a dickhead. They voted for him in spite of it. My cousin's wife's parents are old school Virginia Republican. When my mom (die hard SoCal urban Clinton supporter) asked her who they were voting for she said (back in May) "Well, it looks like it may be Donald Trump". These are normal, nice, non-racist people. But they are economically conservative Republicans. Hillary Clinton and the Democrats don't represent their values and while they may not like Donald Trump's comments, those aren't their core issues.

If you are Pro-2A, you don't care about grabbed pussies. You care about keeping another Sotomayer off the Supreme Court. If you're working class and you just missed the line for healthcare subsidies, Obamacare is hitting your wallet hard. You don't care about him saying mean things about some Mexican immigrants being criminals. Those aren't political issues that will affect your life. They're just mean things being said.

Too many young Democrat voters (too many people in general) think voting is a question of feelings and feeling good about yourself at the end. It's not. And this is why Trump won. His voters don't care that he's a meaniehead. Winning the Presidential Election is about convincing the common schlub that he or she is voting in his or her own best interests. And I mean thinking. It doesn't matter if that isn't actually true. perception is reality.

On RTT Times

From u/Pro_Redditor on a thread on interesting truths

Yeah how the hell does my internet have lower ping than my brain?

On Sorting

Our email inbox typically displays the top fifty messages of potentially thousands, sorted by time of receipt. When we look for restaurants on Yelp we're shown the top dozen or so of hundreds, sorted by proximity or by rating. A blog shows a cropped list of articles, sorted by date. The Facebook news feed, Twitter stream, and Reddit homepage all present themselves as lists, sorted by some proprietary measure. We refer to things like Google and Bing as "search engines," but that is something of a misnomer: they're really sort engines. What makes Google so dominant as a means of accessing the world's information is less that it finds our text within hundreds of millions of webpages-its 1990s competitors could generally do that part well enough-but that it sorts those webpages so well, and only shows us the most relevant ten.

The truncated top of an immense, sorted list is in many ways the universal user interface.

On Vagueness

From Sorites Paradox

For example, the concept of a heap appears to lack sharp boundaries and, as a consequence of the subsequent indeterminacy surrounding the extension of the predicate 'is a heap', no one grain of wheat can be identified as making the difference between being a heap and not being a heap. Given then that one grain of wheat does not make a heap, it would seem to follow that two do not, thus three do not, and so on. In the end it would appear that no amount of wheat can make a heap. We are faced with paradox since from apparently true premises by seemingly uncontroversial reasoning we arrive at an apparently false conclusion.

On Pseudoscience

From: The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark." - really, the whole book is full of amazing excerpts. An absolute must read.

If we teach only the findings and products of science - no matter how useful and even inspiring they may be - without communicating its critical method, how can the average person possibly distinguish science from pseudoscience? Both then are presented as unsupported assertion. In Russia and China, it used to be easy. Authoritative science was what the authorities taught. The distinction between science and pseudoscience was made for you. No perplexities needed to be muddled through. But when profound political changes occurred and strictures on free thought were loosened, a host of confident or charismatic claims - especially those that told us what we wanted to hear - gained a vast following. Every notion, however improbable, became authoritative

On HackerNews Comments

From Dan Luu's Website

Too many to count, basically everything there.

On Equality, Justice, and Social Law

From E. van den Haag, on the death penalty

Maldistribution between the guilty and the innocent is, by definition, unjust. But the injustice does not lie in the nature of the punishment. Because of the finality of the death penalty, the most grievous maldistribution occurs when it is imposed upon the innocent. However, the frequent allegations of discrimination and capriciousness refer to maldistribution among the guilty and not to the punishment of the innocent.

. . .

Equality, in short, seems morally less important than justice. And justice is independent of distributional inequalities. The ideal of equal justice demands that justice be equally distributed, not that it be replaced by equality. Justice requires that as many of the guilty as possible be punished, regardless of whether others have avoided punishment. To let these others escape the deserved punishment does not do justice to them, or to society. But it is not unjust to those who could not escape.

On Explore vs. Exploit

Thinking about children as simply being at the transitory exploration stage of a lifelong algorithm might provide some solace for parents of preschoolers. (Tom has two highly exploratory preschool-age daughters, and hopes they are following an algorithm that has minimal regret.) But it also provides new insights about the rationality of children. Gopnik points out that "if you look at the history of the way that people have thought about children, they have typically argued that children are cognitively deficient in various ways-because if you look at their exploit capacities, they look terrible. They can't tie their shoes, they're not good at long-term planning, they're not good at focused attention. Those are all things that kids are really awful at." But pressing buttons at random, being very interested in new toys, and jumping quickly from one thing to another are all things that kids are really great at. And those are exactly what they should be doing if their goal is exploration. If you're a baby, putting every object in the house into your mouth is like studiously pulling all the handles at the casino.

More generally, our intuitions about rationality are too often informed by exploitation rather than exploration. When we talk about decision-making, we usually focus just on the immediate payoff of a single decision-and if you treat every decision as if it were your last, then indeed only exploitation makes sense. But over a lifetime, you're going to make a lot of decisions. And it's actually rational to emphasize exploration-the new rather than the best, the exciting rather than the safe, the random rather than the considered-for many of those choices, particularly earlier in life.

On Selection

From David Hume

All these suppositions are consistent and conceivable. Why should we give the preference to one, which is no more consistent or conceivable than the rest?

Anecdotes vs. Statistics

When we need to make sense of, say, national health care reform-a vast apparatus too complex to be readily understood-our political leaders typically offer us two things: cherry-picked personal anecdotes and aggregate summary statistics. The anecdotes, of course, are rich and vivid, but they're unrepresentative. Almost any piece of legislation, no matter how enlightened or misguided, will leave someone better off and someone worse off, so carefully selected stories don't offer any perspective on broader patterns. Aggregate statistics, on the other hand, are the reverse: comprehensive but thin. We might learn, for instance, whether average premiums fell nationwide, but not how that change works out on a more granular level: they might go down for most but, Omelas-style, leave some specific group-undergraduates, or Alaskans, or pregnant women-in dire straits. A statistic can only tell us part of the story, obscuring any underlying heterogeneity. And often we don't even know which statistic we need.

On Altruism

From Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

This thesis that what motivates us to act is always a desire should be accepted only if we have a good understanding of what a desire is. If a desire is simply identified with whatever internal state moves someone to act, then the claim, "what motivates us to act is always a desire", when spelled out more fully, is a tautology. It says: "the internal state that moves us to act is always the internal state that moves us to act". That is not a substantive insight into human psychology, but a statement of identity, of the form "A = A". We might have thought we were learning something about what causes action by being told, "what motivates people is always a desire", but if "desire" is just a term for whatever it is that motivates us, we are learning nothing (see Nagel 1970: 27-32).

. . .

To take matters to an extreme, it might be suggested that our ultimate motivation is always entirely other-regarding. According to this far-fetched hypothesis, whenever we act for our own good, we do so not at all for our own sake, but always entirely for the sake of someone else. The important point here is that the denial that altruism exists should be regarded with as much suspicion as this contrary denial, according to which people never act ultimately for their own good. Both are dubious universal generalizations. Both have far less plausibility than the common sense assumption that people sometimes act in purely egoistic ways, sometimes in purely altruistic ways, and often in ways that mix, in varying degrees, the good of oneself and the good of others

On Certainty

From John Stuart Mill

There is no such thing as absolute certainty, but there is assurance sufficient for the purposes of human life.

On Information

From The Information

For the purposes of science, information had to mean something special. Three centuries earlier, the new discipline of physics could not proceed until Isaac Newton appropriated words that were ancient and vague-force, mass, motion, and even time-and gave them new meanings. Newton made these terms into quantities, suitable for use in mathematical formulas. Until then, motion (for example) had been just as soft and inclusive a term as information. For Aristotelians, motion covered a far-flung family of phenomena: a peach ripening, a stone falling, a child growing, a body decaying. That was too rich. Most varieties of motion had to be tossed out before Newton's laws could apply and the Scientific Revolution could succeed. In the nineteenth century, energy began to undergo a similar transformation: natural philosophers adapted a word meaning vigor or intensity. They mathematicized it, giving energy its fundamental place in the physicists' view of nature. It was the same with information. A rite of purification became necessary. And then, when it was made simple, distilled, counted in bits, information was found to be everywhere. Shannon's theory made a bridge between information and uncertainty; between information and entropy; and between information and chaos. It led to compact discs and fax machines, computers and cyberspace, Moore's law and all the world's Silicon Alleys. Information processing was born, along with information storage and information retrieval. People began to name a successor to the Iron Age and the Steam Age. "Man the food-gatherer reappears incongruously as information-gatherer," remarked Marshall McLuhan in 1967.* He wrote this an instant too soon, in the first dawn of computation and cyberspace.

On Timezones

From Thomas Browne, c. 1640

... it being no ordinary or Almanack business, but a probleme Mathematical, to finde out the difference of hours in different places; nor do the wisest exactly satisfy themselves in all. For the hours of several places anticipate each other, according to their Longitudes; which are not exactly discovered of every place.

On Writing

From James Gleick

With words we begin to leave traces behind us like breadcrumbs: memories in symbols for others to follow. Ants deploy their pheromones, trails of chemical information; Theseus unwound Ariadne's thread. Now people leave paper trails. Writing comes into being to retain information across time and across space. Before writing, communication is evanescent and local; sounds carry a few yards and fade to oblivion. The evanescence of the spoken word went without saying. So fleeting was speech that the rare phenomenon of the echo, a sound heard once and then again, seemed a sort of magic. "This miraculous rebounding of the voice, the Greeks have a pretty name for, and call it Echo," wrote Pliny. "The spoken symbol," as Samuel Butler observed, "perishes instantly without material trace, and if it lives at all does so only in the minds of those who heard it." Butler was able to formulate this truth just as it was being falsified for the first time, at the end of the nineteenth century, by the arrival of the electric technologies for capturing speech. It was precisely because it was no longer completely true that it could be clearly seen. Butler completed the distinction: "The written symbol extends infinitely, as regards time and space, the range within which one mind can communicate with another; it gives the writer's mind a life limited by the duration of ink, paper, and readers, as against that of his flesh and blood body."

On Action

From Ward Just, 2004

Odysseus wept when he heard the poet sing of his great deeds abroad because, once sung, they were no longer his alone. They belonged to anyone who heard the song.

On Personal Success

By Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert

If you want an average successful life, it doesn't take much planning. Just stay out of trouble, go to school, and apply for jobs you might like. But if you want something extraordinary, you have two paths:

Become the best at one specific thing. Become very good (top 25%) at two or more things. The first strategy is difficult to the point of near impossibility. Few people will ever play in the NBA or make a platinum album. I don't recommend anyone even try.

The second strategy is fairly easy. Everyone has at least a few areas in which they could be in the top 25% with some effort. In my case, I can draw better than most people, but I'm hardly an artist. And I'm not any funnier than the average standup comedian who never makes it big, but I'm funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes. It's the combination of the two that makes what I do so rare. And when you add in my business background, suddenly I had a topic that few cartoonists could hope to understand without living it.

. . .

Get a degree in business on top of your engineering degree, law degree, medical degree, science degree, or whatever. Suddenly you're in charge, or maybe you're starting your own company using your combined knowledge.

Capitalism rewards things that are both rare and valuable. You make yourself rare by combining two or more "pretty goods" until no one else has your mix...

It sounds like generic advice, but you'd be hard pressed to find any successful person who didn't have about three skills in the top 25%.

On Perfect Secret Sharing

From Adi Shamir's 1979 Perfect Secret Sharing paper

Some of the useful properties of this (k, n) threshold scheme (when compared to the mechanical locks and keys solutions) are:

(1) The size of each piece does not exceed the size of the original data.

(2) When k is kept fixed, D~ pieces can be dynamically added or deleted (e.g., when executives join or leave the company) without affecting the other D i pieces. (A piece is deleted only when a leaving executive makes it completely inaccessible, even to himself.)

(3) It is easy to change the D i pieces without changing the original data D-all we need is a new polynomial q(x) with the same free term. A frequent change of this type can greatly enhance security since the pieces exposed by security breaches cannot be accumulated unless all of them are values of the same edition of the q(x) polynomial.

(4) By using tuples of polynomial values as Di pieces, we can get a hierarchical scheme in which the number of pieces needed to determine D depends on their importance. For example, if we give the company's president three values of q(x), each vice-president two values of q(x), and each executive one value of q(x), then a (3, n) threshold scheme enables checks to be signed either by any three executives, or by any two executives one of whom is a vice-president, or by the president alone.

On luck, chance and meritocracies

Excerpt From: Robert H. Frank. "Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy.

Consider a contest that is completely meritocratic in the sense of being settled on the basis of objective performance alone, and suppose that 98 percent of each contestant's performance is accounted for by talent and effort, only 2 percent by luck. Given these weights, it's clear that no one could win without being both highly talented and hardworking. But less obvious, perhaps, is that the winner is also likely to have been among the luckiest of all contestants. Luck matters so much in contests like these because winning requires that almost everything go right. There will inevitably be many contestants close to the top of the talent and effort scale, and at least some of them are bound to have been lucky as well. So even when luck has only a minor influence on performance, the most talented and hardworking of all contestants will usually be outdone by a rival who is almost as talented and hardworking but also considerably luckier. As we'll see, if we simulated the outcome of this specific contest a thousand times, only a small minority of winners would have higher combined skill and effort levels than all other contestants.

On alternate view points and online discussions

From RIP Culture War Thread - the whole post is worth a read.

Some people think society should tolerate pedophilia, are obsessed with this, and can rattle off a laundry list of studies that they say justify their opinion. Some people think police officers are enforcers of oppression and this makes them valid targets for violence. Some people think immigrants are destroying the cultural cohesion necessary for a free and prosperous country. Some people think transwomen are a tool of the patriarchy trying to appropriate female spaces. Some people think Charles Murray and The Bell Curve were right about everything. Some people think Islam represents an existential threat to the West. Some people think women are biologically less likely to be good at or interested in technology. Some people think men are biologically more violent and dangerous to children. Some people just really worry a lot about the Freemasons.

Each of these views has adherents who are, no offense, smarter than you are. Each of these views has, at times, won over entire cultures so completely that disagreeing with them then was as unthinkable as agreeing with them is today. I disagree with most of them but don't want to be too harsh on any of them. Reasoning correctly about these things is excruciatingly hard, trusting consensus opinion would have led you horrifyingly wrong throughout most of the past, and other options, if they exist, are obscure and full of pitfalls. I tend to go with philosophers from Voltaire to Mill to Popper who say the only solution is to let everybody have their say and then try to figure it out in the marketplace of ideas.

But none of those luminaries had to deal with online comment sections.

The thing about an online comment section is that the guy who really likes pedophilia is going to start posting on every thread about sexual minorities "I'm glad those sexual minorities have their rights! Now it's time to start arguing for pedophile rights!" followed by a ten thousand word manifesto. This person won't use any racial slurs, won't be a bot, and can probably reach the same standards of politeness and reasonable-soundingness as anyone else. Any fair moderation policy won't provide the moderator with any excuse to delete him. But it will be very embarrassing for to New York Times to have anybody who visits their website see pro-pedophilia manifestos a bunch of the time.

"So they should deal with it! That's the bargain they made when deciding to host the national conversation!"

No, you don't understand. It's not just the predictable and natural reputational consequences of having some embarrassing material in a branded space. It's enemy action.

Every Twitter influencer who wants to profit off of outrage culture is going to be posting 24-7 about how the New York Times endorses pedophilia. Breitbart or some other group that doesn't like the Times for some reason will publish article after article on New York Times' secret pro-pedophile agenda. Allowing any aspect of your brand to come anywhere near something unpopular and taboo is like a giant Christmas present for people who hate you, people who hate everybody and will take whatever targets of opportunity present themselves, and a thousand self-appointed moral crusaders and protectors of the public virtue. It doesn't matter if taboo material makes up 1% of your comment section; it will inevitably make up 100% of what people hear about your comment section and then of what people think is in your comment section. Finally, it will make up 100% of what people associate with you and your brand. The Chinese Robber Fallacy is a harsh master; all you need is a tiny number of cringeworthy comments, and your political enemies, power-hungry opportunists, and 4channers just in it for the lulz can convince everyone that your entire brand is about being pro-pedophile, catering to the pedophilia demographic, and providing a platform for pedophile supporters. And if you ban the pedophiles, they'll do the same thing for the next-most-offensive opinion in your comments, and then the next-most-offensive, until you've censored everything except "Our benevolent leadership really is doing a great job today, aren't they?" and the comment section becomes a mockery of its original goal.

And a corresponding criticism of the above rationale

On status as a service

This whole article is worth a read.

Why does proof of work matter for a social network? If people want to maximize social capital, why not make that as easy as possible?

As with cryptocurrency, if it were so easy, it wouldn't be worth anything. Value is tied to scarcity, and scarcity on social networks derives from proof of work. Status isn't worth much if there's no skill and effort required to mine it. It's not that a social network that makes it easy for lots of users to perform well can't be a useful one, but competition for relative status still motivates humans. Recall our first tenet: humans are status-seeking monkeys. Status is a relative ladder. By definition, if everyone can achieve a certain type of status, it's no status at all, it's a participation trophy.

In the annals of tech, and perhaps the world, the event that created the greatest social capital boom in history was the launch of Facebook's News Feed.

Before News Feed, if you were on, say MySpace, or even on a Facebook before News Feed launched, you had to browse around to find all the activity in your network. Only a demographic of a particular age will recall having to click from one profile to another on MySpace while stalking one's friends. It almost seems comical in hindsight, that we'd impose such a heavy UI burden on social media users. Can you imagine if, to see all the new photos posted in your Instagram network, you had to click through each profile one by one to see if they'd posted any new photos? I feel like my parents talking about how they had to walk miles to grade school through winter snow wearing moccasins of tree bark when I complain about the undue burden of social media browsing before the News Feed, but it truly was a monumental pain in the ass.

By merging all updates from all the accounts you followed into a single continuous surface and having that serve as the default screen, Facebook News Feed simultaneously increased the efficiency of distribution of new posts and pitted all such posts against each other in what was effectively a single giant attention arena, complete with live updating scoreboards on each post. It was as if the panopticon inverted itself overnight, as if a giant spotlight turned on and suddenly all of us performing on Facebook for approval realized we were all in the same auditorium, on one large, connected infinite stage, singing karaoke to the same audience at the same time.

It's difficult to overstate what a momentous sea change it was for hundreds of millions, and eventually billions, of humans who had grown up competing for status in small tribes, to suddenly be dropped into a talent show competing against EVERY PERSON THEY HAD EVER MET.

. . .

Yet, I come not to bury Caesar, but also not to praise him. Rather, as Emily Wilson says at the start of her brilliant new translation of The Odyssey, "tell me about a complicated man." So much of the entire internet was built on a foundation of social capital, of intangible incentives like reputation. Before the tech giants of today, I combed through newsgroups, blogs, massive FAQs, and countless other resources built by people who felt, in part, a jolt of dopamine from the recognition that comes from contributing to the world at large. At Amazon, someone coined a term for this type of motivational currency: egoboo (short for, you guessed it, egoboost). Something like Wikipedia, built in large part on egoboo, is a damned miracle. I don't want to lose that. I don't think we have to lose that.

On social media archetypes

From The Evaporative Cooling Effect

There are two fundamental patterns of social organization which I term "plaza" and "warrens". In the plaza design, there is a central plaza which is one contiguous space and every person's interaction is seen by every other person. In the warren design, the space is broken up into a series of smaller warrens and you can only see the warren you are currently in. There is the possibility of moving into adjacent warrens but it's difficult to explore far outside of your zone. Plazas grow by becoming larger, warrens grow by adding more warrens.

These are the two fundamental patterns of social spaces. Every social space can be decomposed down to a collection of plazas and warrens. In Facebook, your profile, friends and newsfeeds are warrens but fan pages, groups & events are plazas. Twitter is mostly a warren with the exception of trending topics which is the one plaza. On forums, the front page and topic listings are plazas but each forum thread is a warren.

Plazas and warrens both have their unique set of tradeoffs. Warrens are notoriously difficult to get started. New users, stuck in empty warrens often don't know how to connect to hubs of activity. The onboarding process is crucial and still not well understood (Friendfeed found that people needed to add at least 5 friends to have a reasonable chance of sticking with the service). On the other hand, plazas only need to be started once and then they remain a hive of activity for new users to participate in from the first day.

Plazas are much more visible than warrens so it's easier to watch and understand your community. In communities, like in justice, sunlight is often the best disinfectant and the neglected spaces often become thriving breeding grounds for all sorts of social pathologies.

But the one absolute killer feature of warrens is that they allow your community to become almost perfectly scale free and grow like mad without ever sacrificing quality. This alone, makes them a design element that's heavily worth studying to figure out what are the good social designs.

It's also interesting to note that the real world is intrinsically warren while the online world is intrinsically plaza. In real life interactions, the physics of sound mean that we can only ever talk to a few people at once. Every person gets a "personalized" social life. To give every person the exact same content takes special work. Online, the easiest model to program is to serve the exact same bits to every requester. To provide "personalized" content takes special work. It is interesting to observe how this difference has influenced the evolution of these two mediums.

On information and propaganda

What [Walter] Lippmann took from the war - as he explained in his 1922 classic Public Opinion - was the gap between the true complexity of the world and the narratives the public uses to understand it - the rough "stereotypes" (a word he coined in his book). When it came to the war, he believed that the "consent" of the governed had been, in his phrase, "manufactured". Hence, as he wrote, 'It is no longer possible... To believe in the original dogma of democracy; that the knowledge needed for the management of human affairs comes up spontaneously from the human heart. Where we act on that theory we expose ourselves to self deception, and to forms of persuasion that we cannot verify.'

Any communication, Lippmann came to see, is potentially propagandistic, in the sense of propagating a view. For it presents on set of facts, or one perspective, fostering or weakening some "stereotype" held by the mind. It is fair to say, then, that any and all information that one consumes - pays attention to - will have some influence, even if just forcing a reaction. That idea, in turn, has a very radical implication, for it suggests that sometimes we overestimate our own capacity for truly independent thought. In most areas of life, we necessarily rely on others for the presentation of facts and ultimately choose between manufactured alternatives, whether it is our evaluation of a product or a political proposition. And if that is true, in the battle for our attention, there is a particular importance in who gets there first or most often. The only communications truly without influence are those that one learns to ignore or never hears at all; (emphasis mine) this is why Jacques ellul argued that it is only the disconnected - rural dwellers or the urban poor - who are truly immune to propaganda, while intellectuals, who read everything, insist on having opinions, and think themselves immune to propaganda are, in fact, easy to manipulate.

On informational unity and trust

From What the hell is going on

The Broadcast era was shaped by high barriers to entry, which centralized the entire media industry. At the peak of the Broadcast Era in the 1960s, fewer than 25 companies monopolized the information cables of radio, television, books, magazines, and music.

There were four television networks, five book publishing houses, five record companies, and seven motion picture studios that controlled most of what America consumed. Powerful and authoritative, these media conglomerates shaped the hearts and minds of millions of Americans. They shaped narratives and controlled ideologies. Information flowed in one direction, from producer to consumer.

No individual illustrates the media's all-encompassing influence better than Walter Cronkite. "The Most Trusted Man in America" served as an anchorman for the CBS Evening News for 19 years. Cronkite's nickname was rooted in fact. According to The Quayle Poll, a survey which measured trust in public figures, Cronkite sat at the top of the list and was the only newsman to appear on it. Everybody else on the list of trusted people was a politician. Yes, you read that right. Times have changed.

Sitting at the nexus of American television, Cronkite covered every NASA space shot, from the early Mercury launches, to the Apollo 8's jaw-dropping, eye-watering orbit around the dark side of the Moon; he covered every major national event from the elation of America's bicentennial celebration to the despair of the Kennedy assassination. When Cronkite spoke, America listened. In 1968, Cronkite traveled to Southeast Asia, where he barely escaped from Saigon alive, to interview generals and G.Is, and see the Vietnam War with his own eyes.

In 1965, Americans consented to the Vietnam War. An October 1965 poll showed that 64 percent of Americans approved of the involvement in Vietnam. Spurred by Cronkite, the tenor of American opinions reversed. And by January 1969, 52 percent thought the Vietnam War was a mistake.

How did American opinions change so fast?

In his 1968 "Report from Vietnam," a CBS news special, Cronkite didn't just report the facts. With words that would alter the course of a nation, he criticized the war and described it as a stalemate.

Back on the American mainland, chomping at his nails with nervous trepidation, President Lyndon B. Johnson watched Cronkite's broadcast.

His hair greying by the second, the President stooped towards the television, as his back slouched like the fallen soldiers before his eyes. LBJ sensed a shifting tide. Heart pumping, legs bouncing, eyes glued to Cronkite's live report, President Johnson said to his press secretary: "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America." Everything changed. One man. One night. One report. In a centralized media environment, that's all it took to sway American consciousness and alter the course of an international war.

In typical fashion, Walter Cronkite concluded his CBS Evening News Broadcasts with his famous closing words: "And that's the way it is." Speaking with the authority of God, Cronkite's words laid the ground-truth narrative from which all other discussion followed. A little more than a month after Cronkite's broadcast, on Sunday, Marsh 31st, Johnson announced he would not seek another term as President.

. . .

Like a coxswain yelling to his team of obedient rowers, leaders controlled the dissemination of information and determined the movement of the entire group. Even as global population skyrocketed from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 6 billion in 2000, media driven cohesion kept the group together. Millions of people moved in near-magical synchronicity. Stroke! Stroke! Stroke!

Even if it was distorted, the masses were united by a shared reality. As long as people rowed at the same speed, society thrived. This strategy of simplifying information flows and ignoring the many shades of complexity with black and white interpretations of the news was extremely successful. So successful, in fact, that in the 20th century, America led the greatest wealth creation boom in human history. We replaced horses with cars, steam with oil, shacks with skyscrapers, trails with highways, and candles with electricity. For the most part, it was a massive success.

On optimization and modern technological approaches

From "Optimize what?", Commune Mag.

It is by now common sense that technical education gives rise to techno-solutionism-that a curriculum expounding the primacy of code and symbolic manipulations begets graduates who proceed to tackle every social problem with software and algorithms. While true, this misses the mark about what the engineering academy fundamentally teaches. The students and instructor in the ethics course were discussing a matter of politics and policy as if it were a technical problem. The issue, then, lay in their conception of the entire exercise: they reflexively committed to saving an unworkable representative democracy, and consigned themselves to inventing a clever mechanism to encourage desirable election outcomes. Techno-solutionism is the very soul of the neoliberal policy designer, fetishistically dedicated to the craft of incentive alignment and (when necessary) benevolent regulation. (emphasis mine) Such a standpoint is the effective outcome of the contemporary computational culture and its formulation as curriculum.

. . .

Boyd teaches this course once a year, and typically in the first lecture, he declares: "Everything is an optimization problem." The claim reeks of techno-utilitarian naivete, with its suggestion that every object can be modeled as a bunch of numbers, every human desire expressed in a utility function, every problem resolvable using the more or less crude calculation devices in our pockets. Yet for the four hundred students enrolled in the winter 2019 offering of this course-mostly PhD and Master's students in computer science, electrical engineering, and applied mathematics-these assumptions underpin everything they have learned for the better part of a decade. For them, the statement is not just true, it's banal.

On beauty

From A Natural History of Beauty

Dandelion head: single or multiplayer beauty?

A: neither. The fact that we find this part of a dandelion beautiful is largely a coincidence - a spandrel. Certainly the dandelion head didn't evolve for us: it's a device for scattering seeds on the wind, not a lure for us (or any animal) to engage with it. Nor, I think, did we evolve any special eyes for the dandelion. Instead, dandelions give off perceptual cues (like symmetry and repetition of form) that happen to coincide with strategies used by bona fide Beauty players for which we may have coevolved an appreciation.

Note that this shouldn't in any way tarnish our appreciation of the dandelion. Whatever the underlying cause, it still tickles the beauty centers in our brains. But insofar as we're calling attention to the game mechanics that underlie beauty, it must be noted that there's no coupling between our desire circuits and the dandelion form. Neither is chasing the other.

In fact, the same can be said for our relationship to flowers more generally. Flowers are playing multiplayer beauty with pollinators, clearly, but why they happen to appeal to us is a fascinating open question.

. . .

What about sexual selection? Is it driven by Independent or Correlated Desire?

This turns out to be quite the contentious issue, and the literature is split more or less down the middle.

To illustrate the two camps, let's take the concrete question of why peahens (female Desire players) are attracted to peacocks (male Beauty players):

One story goes like this:

A peacock's tail serves as an honest signal of his genetic fitness and therefore his quality as a mate. In order to grow something so big and bright and highly-ordered, the peacock must be a hearty specimen with good genes. And thus the benefit to the peahen is fairly straightforward: by choosing a beautiful mate, she'll tend to have healthier, heartier offspring - who will, in turn, leave her more grandchildren.

In this story, peahens are playing a game of Independent Desire. Each gets to choose the mate she considers the healthiest (i.e., most beautiful), without regard to what her peers are doing.

The other story goes like this:

A peacock's tail is not an honest signal of his fitness. Whatever heartiness is required to produce the tail is cancelled out by the hassle of lugging it around - so males with small, drab tails are just as good at surviving as males with big, bright ones. Instead, a peahen who desires flashy tails is rewarded because other peahens also desire those tails - and therefore the sons that she makes with her beautiful mate will tend to be desired when it's their turn to reproduce.

In evolutionary biology, this is called runaway sexual selection. And if it sounds circular, well, that's because it is. In runaway selection, the initial female desire is entirely arbitrary, but it gets fixed within a population simply because everyone else is doing it. Think of it as a self-reinforcing popularity loop. There may be no reason for the initial popularity, but once bright tails become popular, they can remain popular indefinitely (because any female who mates with an ugly/ unpopular mate will have ugly/ unpopular sons). This is a game of Correlated Desire.

So then, in the case of peafowl, which is it? Did the peacock's tail evolve in response to Independent Desire (honest signaling) or Correlated Desire (runaway selection)?

At the risk of being a wet blanket, I suspect it's a bit of both. So instead of trying to adjudicate, I'd like to make some general remarks about how to determine which type of game is being played, Independent or Correlated Desire.

On the Desire side, games of Correlated Desire reward herdthink. In sexual selection, we see this as mate choice copying, where females watch other females to see which males they choose, then copy the most popular choices.5 In the human realm, herdthink shows up as mimetic desire, where people want things largely because other people want them as well.6

But what about the Beauty side? Do the forms of beauty that evolve in the two types of games differ in systematic ways? Perhaps, although I don't know how strong the effect is. In games of Independent Desire, beauty solves a concrete problem: how to induce a Desire player into a relationship with a Beauty player. And thus there are constraints on the forms that such beauty can take. For example, a flower has to be bright and stand out from the background in order for pollinators to see it from afar. However, in games of Correlated Desire, the objects desired by the herd can take on more arbitrary forms, resulting in a kind of hollow or degenerate beauty - things that are desired only because everyone else desires them (or is thought to desire them), rather than for their intrinsic qualities. (See for example much of contemporary art and architecture.) In these cases, beauty can persist because of the network effect (self-reinforcing popularity), but there's nevertheless something fragile about it. Biology nerds may recognize this as the lek paradox, while economists will see some of the problems with fiat currencies (e.g., that governments often have to prop them up by artificial means). In both domains, the desire will be more stable if the object in question has even a touch of intrinsic value: gene quality in the case of sexually-selected ornaments; rare metals in the case of money.

On dark pools, HFT, and the US market in early 2010's

From Flash Boys by Michael Lewis

[On HFT firms] "I hate [HFT firms] a lot less than before we started," said Brad. "This is not their fault. I think most of them have just rationalized that the market is creating inefficiencies and they are just capitalizing on them. Really, it's brilliant what they have done within the bounds of the regulation. They are much less of a villain than I thought. The system has let down the investor."

. . .

Technology had collided with Wall Street in a peculiar way. It had been used, as it should have been used, to increase efficiency. But it had also been used to introduce a peculiar sort of market inefficiency. This new inefficiency was not like the inefficiencies that financial markets can easily correct. After a big buyer enters the market and drives up the price of Brent crude oil, for example, it's healthy and good when speculators jump in and drive up the price of North Texas crude, too. It's healthy and good when traders see the relationship between the price of crude oil and the price of oil company stocks, and drive these stocks higher. It's even healthy and good when some clever high-frequency trader divines a necessary statistical relationship between the share prices of Chevron and Exxon, and responds when it gets out of whack. It was neither healthy nor good when public stock exchanges introduced order types and speed advantages that high-frequency traders could use to exploit everyone else. This sort of inefficiency didn't vanish the moment it was spotted and acted upon. It was like a broken slot machine in the casino that pays off every time. It would keep paying off until someone said something about it; but no one who played the slot machine had any interest in pointing out that it was broken.

On linguistic ambiguities, superposition of definitions, and what "is" is

From Wordy Weapons of Is-Ought Alloy

To agree that a word accurately describes a thing is to agree that a whole set of attitudes and associated actions should be applied to it. What is and what isn't "theft", "hate speech", "torture", "terrorism" or "eugenics" is one of substance, sure, but perhaps more importantly one of consequences. If accused of a crime there may or may not be something bad you have in fact done, but in the end it is the label that sticks - guilty or not guilty - that determines what happens to you. Other labels come with less stark consequences, but with consequences they come.

The lyrics to Wonderful performed by the "wonderful" Wizard of Oz in the musical Wicked is a wonderfully (sic) cute illustration of the power of labels:

A man's called a traitor or liberator. A rich man's a thief, or philanthropist. Is one a crusader, or ruthless invader? It's all in which label is able, to persist. There are precious few at ease with moral ambiguities, so we act as though they don't exist. They call me wonderful, so I am wonderful. In fact it's so much who I am, it's part of my name, and with my help, you can be the same.

(Couldn't resist that, I'm a sucker for clever rhyming.)

Labels sort individual cases into predefined buckets for easy parsing and propagation. This is how minds work. This is efficient. This is a good thing. A necessary thing. We save effort when we think and we save bandwidth when we communicate by using preset concepts instead of preserving full complexity and nuance. We have not the time, not the inclination, and not the processing power to communicate using anything more than a caricature of reality.

Given all this, of course we'd like to control what labels are in use and what connotations and associated actions they have. We'd be stupid not to try.

Arguing semantics are often derided, but it shouldn't be. Telling someone not to argue semantics is to imply that they should accept whatever vocabulary is given to them, i.e. accept to have the terms of debate dictated to them. That's often tantamount to begging the question, since a lot of public discourse is dedicated to shaping the meaning of labels and getting them to stick to certain things (and to resisting and disrupting your enemies' attempts to do this). That's PR. That's rhetoric. But not traditonal, "focused" rhetoric where a man in a toga tries to convince the senate to launch an invasion. This "unfocused rhetoric" isn't about some specific decision, it's about influencing the background memetic environment to be more favourable to your interests.

In other words it's not pure "ought" as in "we should do this", because it gets elements of "is" when it tells us to adopt a particular model of reality and its associated vocabulary.

. . .

An encounter with an ambiguous yet controversial-sounding claim starts with an instinctive emotional reaction. We infer the intentions or agenda behind the claim, interpret it in the way most compatible with our own attitude, and then immediately forget the second step ever happened and confuse the intended meaning with our own interpretation. This is a complicated way of saying that if you feel a statement is part of a rival political narrative you'll unconsciously interpret it to mean something false or unreasonable, and then think you disagree with people politically because they say false and unreasonable things.

On the signal and corrective

From The Signal and the Corrective

Most people have somewhat moderate views and they recognize that there is a bit of truth to both of two apparently opposing narratives. This can mask fundamental differences between those appearing to be in agreement.

Like, look at [a] zebra.

We can all agree on what it looks like. But some of us will think of it as a white horse with black stripes and some as a black horse with white stripes, and while it doesn't actually matter now, that might change if whether "zebras are fundamentally white" or "zebras are fundamentally black" ever becomes an issue of political importance.

In the real world zebras are (thank God) still politically neutral, but similar patterns exist. Two people with political views like:

"The free market is extremely powerful and will work best as a rule, but there are a few outliers where it won't, and some people will be hurt so we should have a social safety net to contain the bad side effects."

and

"Capitalism is morally corrupt and rewards selfishness and greed. An economy run for the people by the people is a moral imperative, but planned economies don't seem to work very well in practice so we need the market to fuel prosperity even if it is distasteful."

. . . have very different fundamental attitudes but may well come down quite close to each other in terms of supported policies. If you model them as having one "main signal" (basic attitude) paired with a corrective to account for how the basic attitude fails to match reality perfectly, then this kind of difference is understated when the conversation is about specific issues (because then signals plus correctives are compared and the correctives bring "opposite" people closer together) but overstated when the conversation is about general principles - because then it's only about the signal.

The funny sad thing is that this supports the view that if we saw every issue on its own terms instead of part of a Big Referendum on Which Side is Right About Everything then we would agree more and fight less (which is part of the reason politics gets less terrible as it gets more local).

It also explains the sort of situation (which happens to me a lot) where you switch sides based on who you're talking to. If you're with someone with an opposite signal, you prioritize boosting your own signal and ignore your own corrective that actually agrees with the other person. However, when talking to someone who agrees with your signal you may instead start to argue for your corrective. And if you're in a social environment where everyone shares your signal and nobody ever mentions a corrective you'll occasionally be tempted to defend something you don't actually support (but typically you won't because people will take it the wrong way). My "defense" of the concept "War on Christmas" from last year is an example of that.

The model gives us a new way to characterize zealots or ideologues (they're people without correctives) and groupthink (that's when correctives are not allowed). Such people and such environments creep me out.

Finally, it offers a new perspective on the whole Rand lovers vs. Rand haters thing. Capitalist-types are usually the villains in fiction[3], and how the poor are oppressed by the evil rich has been dramatized so many times that the corrective[4] - that entrepreneurship is crucial for building wealth, capital owners fill a very important function, and the wealth of the industrialized world is disproportionally created by those who innovate and build technological systems - will be jarring when it's for once brought out and given full signal-treatment instead (with the corresponding corrective ignored). It'll feel perverse (or liberating) the same way "medical treatment hurts people who want to die" does in House of God.

On hindsight bias

From Hindsight Devalues Science

Cullen Murphy, editor of The Atlantic, said that the social sciences turn up "no ideas or conclusions that can't be found in [any] encyclopedia of quotations... Day after day social scientists go out into the world. Day after day they discover that people's behavior is pretty much what you'd expect."

Of course, the "expectation" is all hindsight. (Hindsight bias: Subjects who know the actual answer to a question assign much higher probabilities they "would have" guessed for that answer, compared to subjects who must guess without knowing the answer.)

The historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. dismissed scientific studies of World War II soldiers' experiences as "ponderous demonstrations" of common sense. For example:

Better educated soldiers suffered more adjustment problems than less educated soldiers. (Intellectuals were less prepared for battle stresses than street-smart people.) Southern soldiers coped better with the hot South Sea Island climate than Northern soldiers. (Southerners are more accustomed to hot weather.) White privates were more eager to be promoted to noncommissioned officers than Black privates. (Years of oppression take a toll on achievement motivation.) Southern Blacks preferred Southern to Northern White officers. (Southern officers were more experienced and skilled in interacting with Blacks.) As long as the fighting continued, soldiers were more eager to return home than after the war ended. (During the fighting, soldiers knew they were in mortal danger.) How many of these findings do you think you could have predicted in advance? Three out of five? Four out of five? Are there any cases where you would have predicted the opposite-where your model takes a hit? Take a moment to think before continuing...

. . .

In this demonstration (from Paul Lazarsfeld by way of Meyers), all of the findings above are the opposite of what was actually found. How many times did you think your model took a hit? How many times did you admit you would have been wrong? That's how good your model really was. The measure of your strength as a rationalist is your ability to be more confused by fiction than by reality.

Unless, of course, I reversed the results again. What do you think?

Do your thought processes at this point, where you really don't know the answer, feel different from the thought processes you used to rationalize either side of the "known" answer?

Daphna Baratz exposed college students to pairs of supposed findings, one true ("In prosperous times people spend a larger portion of their income than during a recession") and one the truth's opposite. In both sides of the pair, students rated the supposed finding as what they "would have predicted." Perfectly standard hindsight bias.

Which leads people to think they have no need for science, because they "could have predicted" that.

(Just as you would expect, right?)

Hindsight will lead us to systematically undervalue the surprisingness of scientific findings, especially the discoveries we understand-the ones that seem real to us, the ones we can retrofit into our models of the world. If you understand neurology or physics and read news in that topic, then you probably underestimate the surprisingness of findings in those fields too. This unfairly devalues the contribution of the researchers; and worse, will prevent you from noticing when you are seeing evidence that doesn't fit what you really would have expected.

We need to make a conscious effort to be shocked enough.

Also on hindsight bias

From Hindsight Bias

Viewing history through the lens of hindsight, we vastly underestimate the cost of effective safety precautions. In 1986, the Challenger exploded for reasons traced to an O-ring losing flexibility at low temperature. There were warning signs of a problem with the O-rings. But preventing the Challenger disaster would have required, not attending to the problem with the O-rings, but attending to every warning sign which seemed as severe as the O-ring problem, without benefit of hindsight. It could have been done, but it would have required a general policy much more expensive than just fixing the O-Rings.

Shortly after September 11th 2001, I thought to myself, and now someone will turn up minor intelligence warnings of something-or-other, and then the hindsight will begin. Yes, I'm sure they had some minor warnings of an al Qaeda plot, but they probably also had minor warnings of mafia activity, nuclear material for sale, and an invasion from Mars.

Because we don't see the cost of a general policy, we learn overly specific lessons. After September 11th, the FAA prohibited box-cutters on airplanes-as if the problem had been the failure to take this particular "obvious" precaution. We don't learn the general lesson: the cost of effective caution is very high because you must attend to problems that are not as obvious now as past problems seem in hindsight.

The test of a model is how much probability it assigns to the observed outcome. Hindsight bias systematically distorts this test; we think our model assigned much more probability than it actually did. Instructing the jury doesn't help. You have to write down your predictions in advance. Or as Fischhoff (1982) put it:

When we attempt to understand past events, we implicitly test the hypotheses or rules we use both to interpret and to anticipate the world around us. If, in hindsight, we systematically underestimate the surprises that the past held and holds for us, we are subjecting those hypotheses to inordinately weak tests and, presumably, finding little reason to change them.

On the advancement of scientific theories, especially as it relates to subtle meta analysis

From The Control Group is Out of Control

This is the principle behind the Pyramid of Scientific Evidence. The lowest level is your personal opinions, no matter how ironclad you think the logic behind them is. Just above that is expert opinion, because no matter how expert someone is they're still only human. Above that is anecdotal evidence and case studies, because even though you're finally getting out of people's heads, it's still possible for the content of people's heads to influence which cases they pay attention to. At each level, we distill away more and more of the human element, until presumably at the top the dross of humanity has been purged away entirely and we end up with pure unadulterated reality.

And for a while this went well. People would drop things off towers, or see how quickly gases expanded, or observe chimpanzees, or whatever.

Then things started getting more complicated. People started investigating more subtle effects, or effects that shifted with the observer. The scientific community became bigger, everyone didn't know everyone anymore, you needed more journals to find out what other people had done. Statistics became more complicated, allowing the study of noisier data but also bringing more peril. And a lot of science done by smart and honest people ended up being wrong, and we needed to figure out exactly which science that was.

And the result is a lot of essays like this one, where people who think they're smart take one side of a scientific "controversy" and say which studies you should believe. And then other people take the other side and tell you why you should believe different studies than the first person thought you should believe. And there is much argument and many insults and citing of authorities and interminable debate for, if not centuries, at least a pretty long time.

The highest level of the Pyramid of Scientific Evidence is meta-analysis. But a lot of meta-analyses are crap. This meta-analysis got p < 1.2 * 10^-10 for a conclusion I'm pretty sure is false, and it isn't even one of the crap ones. Crap meta-analyses look more like this, or even worse.

On confidence levels and probabilities

From Confidence levels inside and outside an argument

Suppose the people at FiveThirtyEight have created a model to predict the results of an important election. After crunching poll data, area demographics, and all the usual things one crunches in such a situation, their model returns a greater than 999,999,999 in a billion chance that the incumbent wins the election. Suppose further that the results of this model are your only data and you know nothing else about the election. What is your confidence level that the incumbent wins the election?

Mine would be significantly less than 999,999,999 in a billion.

When an argument gives a probability of 999,999,999 in a billion for an event, then probably the majority of the probability of the event is no longer in "But that still leaves a one in a billion chance, right?". The majority of the probability is in "That argument is flawed". Even if you have no particular reason to believe the argument is flawed, the background chance of an argument being flawed is still greater than one in a billion.

More than one in a billion times a political scientist writes a model, they will get completely confused and write something with no relation to reality. More than one in a billion times a programmer writes a program to crunch political statistics, there will be a bug that completely invalidates the results. More than one in a billion times a staffer at a website publishes the results of a political calculation online, ey will accidentally switch which candidate goes with which chance of winning.

So one must distinguish between levels of confidence internal and external to a specific model or argument. Here the model's internal level of confidence is 999,999,999/billion. But my external level of confidence should be lower, even if the model is my only evidence, by an amount proportional to my trust in the model.

On AI safety

From So Far: Unfriendly AI Edition

When you think a goal criterion implies something you want, you may have failed to see where the real maximum lies. When you try to block one behavior mode, the next result of the search may be another very similar behavior mode that you failed to block. This means that safe practice in this field needs to obey the same kind of mindset as appears in cryptography, of "Don't roll your own crypto" and "Don't tell me about the safe systems you've designed, tell me what you've broken if you want me to respect you" and "Literally anyone can design a code they can't break themselves, see if other people can break it" and "Nearly all verbal arguments for why you'll be fine are wrong, try to put it in a sufficiently crisp form that we can talk math about it" and so on. (AI safety mindset)

On expectations of beliefs and stereotypes

What do we do when we expect something factually but not morally?

I tend to believe that stereotypes are broadly accurate, in other words that they capture real and significant clusters of traits and behaviors, for the most part. Factually, then, I expect people to conform to stereotypes more than predicted by chance. But morally I don't. I don't think people are somehow obligated to conform to stereotypes, nor do I resent them when they don't (in fact I quite enjoy that, it replenishes my faith in self-determination and individual agency).

Now, if someone asks me whether I believe some stereotypical claim (or asserts with unjustified confidence that to do so must be wrong), what the hell am I supposed to say? Yes I do expect it to be true, on average. No, I wouldn't consider someone at fault for not conforming to that expectation, nor would I even slightly resist changing it facing contrary evidence.

I know of no way to say this that's short and simple enough to be quickly understood and resistant to hostile interpretation.

On Attention

From The Attention Merchants by Tim Wu

The Nazi regime's extreme, coercive demands on attention oblige us to consider the relationship between control over one's attention and human freedom. Take the most elementary type of freedom, the freedom to choose between choices A and B, say chocolate or vanilla.

The most direct and obvious way authoritarians abridge freedom is to limit or discourage or ban outright certain options - NO CHOCOLATE, for instance. The State might ban alcohol, for example, as the United States once did and a number of Muslim nations still do; likewise it might outlaw certain political parties or bar certain individuals from seeking office. But such methods are blunt and intrusive, as well as imperfect, which is true of any restriction requiring enforcement. It is therefore more effective for the State to intervene before options are seen to exist. This creates less friction with the State but requires a larger effort: total attention control.

Freedom might be said to describe not only the size of our "option set" but also our awareness of what options there are. That awareness has two degrees. One is conceptual: if you don't know about a thing, like chocolate ice cream, you can hardly ask for it, much less feel oppressed by the want of it. The second degree of awareness comes after we know about things conceptually and can begin to contemplate them as real choices. I may be aware that man has gone into space but the idea that I might choose to go there myself, while conceivable is only a notion until I find out that Virgin Galactic has started scheduling flights.

On Equality

From Sapiens

It is easy for us to accept that the division of people into 'superiors' and 'commoners' is a figment of the imagination. Yet the idea that all humans are equal is also a myth. In what sense do all humans equal one another? Is there any objective reality, outside the human imagination, in which we are truly equal? Are all humans equal to one another biologically? Let us try to translate the most famous line of the American Declaration of Independence into biological terms:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

According to the science of biology, people were not 'created'. They have evolved. And they certainly did not evolve to be 'equal'. The idea of equality is inextricably intertwined with the idea of creation. The Americans got the idea of equality from Christianity, which argues that every person has a divinely created soul, and that all souls are equal before God. However, if we do not believe in the Christian myths about God, creation and souls, what does it mean that all people are 'equal'? Evolution is based on difference, not on equality. Every person carries a somewhat different genetic code, and is exposed from birth to different environmental influences. This leads to the development of different qualities that carry with them different chances of survival. 'Created equal' should therefore be translated into 'evolved differently'.

Just as people were never created, neither, according to the science of biology, is there a 'Creator' who 'endows' them with anything. There is only a blind evolutionary process, devoid of any purpose, leading to the birth of individuals. 'Endowed by their creator' should be translated simply into 'born'. Equally, there are no such things as rights in biology. There are only organs, abilities and characteristics. Birds fly not because they have a right to fly, but because they have wings. And it's not true that these organs, abilities and characteristics are 'unalienable'. Many of them undergo constant mutations, and may well be completely lost over time. The ostrich is a bird that lost its ability to fly. So 'unalienable rights' should be translated into 'mutable characteristics'.

And what are the characteristics that evolved in humans? 'Life', certainly. But 'liberty'? There is no such thing in biology. Just like equality, rights and limited liability companies, liberty is something that people invented and that exists only in their imagination. From a biological viewpoint, it is meaningless to say that humans in democratic societies are free, whereas humans in dictatorships are unfree. And what about 'happiness'? So far biological research has failed to come up with a clear definition of happiness or a way to measure it objectively. Most biological studies acknowledge only the existence of pleasure, which is more easily defined and measured. So 'life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness' should be translated into 'life and the pursuit of pleasure'. So here is that line from the American Declaration of Independence translated into biological terms:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men evolved differently, that they are born with certain mutable characteristics, and that among these are life and the pursuit of pleasure.

Advocates of equality and human rights may be outraged by this line of reasoning. Their response is likely to be, 'We know that people are not equal biologically! But if we believe that we are all equal in essence, it will enable us to create a stable and prosperous society.' I have no argument with that. This is exactly what I mean by 'imagined order'. We believe in a particular order not because it is objectively true, but because believing in it enables us to cooperate effectively and forge a better society. Imagined orders are not evil conspiracies or useless mirages. Rather, they are the only way large numbers of humans can cooperate effectively. Bear in mind, though, that Hammurabi might have defended his principle of hierarchy using the same logic: 'I know that superiors, commoners and slaves are not inherently different kinds of people. But if we believe that they are, it will enable us to create a stable and prosperous society.

On Hedge Fund Insider Trading

From More Money than God

Clearly, hedge-fund managers are not angels. Their history is full of blemishes, from Michael Steinhardt's collusive block trading to David Askin's nonexistent mortgage-prepayment model. The very structure of a hedge fund has worried regulators since the early days. At the time of the Douglas Aircraft case, regulators fretted that hedge-fund patrons included rainmakers and senior executives at public firms-what if these well-placed folk leaked privileged facts to the men who looked after their money? Two generations later, these suspicions seem to have been vindicated in the Galleon affair, and it would be naive to suppose that other 1960s misgivings have lost their relevance. The Douglas case showed that the enormous commissions that hedge funds generate for brokers create a potential for abuse, and it's a pretty fair bet that such abuses continue. There are criminals and charlatans in every industry. Hedge funds are no different.

And yet, equally clearly, hedge funds should not be judged against some benchmark of perfection. The case for believing in the industry is not that it is populated with saints but that its incentives and culture are ultimately less flawed than those of other financial companies. There is no evidence, for example, that hedge funds engage in fraud or other abuses more often than rivals. In 2003 an SEC inquiry looked for such evidence and found none; and indeed a freestanding hedge fund is arguably less likely to receive illegal tips than an asset manager housed within a major bank, which is privy to all manner of profitable information fl ows from corporate clients and trading partners. For sensitive news to reach the wrong ears inside a modern financial conglomerate, it merely has to pierce the Chinese walls dividing equity underwriters or merger advisers from proprietary traders. For the news to reach a hedge fund, it has to take the additional step of exiting the building. [Emphasis mine]

What is true for fraud and insider trading is also true for most other accusations leveled at hedge funds: The charges might be better directed against other financial players, as we shall see presently. But the heart of the case for hedge funds can be summed up in a single phrase. Whereas large parts of the financial system have proved too big to fail, hedge funds are generally small enough to fail. When they blow up, they cost taxpayers nothing.

On Relativism and Narratives

From Adaptive Markets

Like the characters in Rashomon, we have to recognize the possibility that complex truths are often in the eye of the beholder. This is a simple fact of human cognition; we've evolved to create narratives to suit our particular needs and desires (recall the left brain's ability to generate narratives). One shouldn't infer from this fact that relativism is correct or desirable. Not all truths are equally valid. However, the particular narrative that one adopts can color and influence the subsequent course of inquiry and debate. We should strive to entertain as many interpretations of the same set of objective facts as we can and hope that a more nuanced and internally consistent understanding of the crisis emergenes in the fullness of time. Some narratives are mistaken, incorrect, or deliberately untrue. Where facts can be verified or refuted, we should do so expeditiously and relentlessly.

On Coincedences

From Ribbonfarm

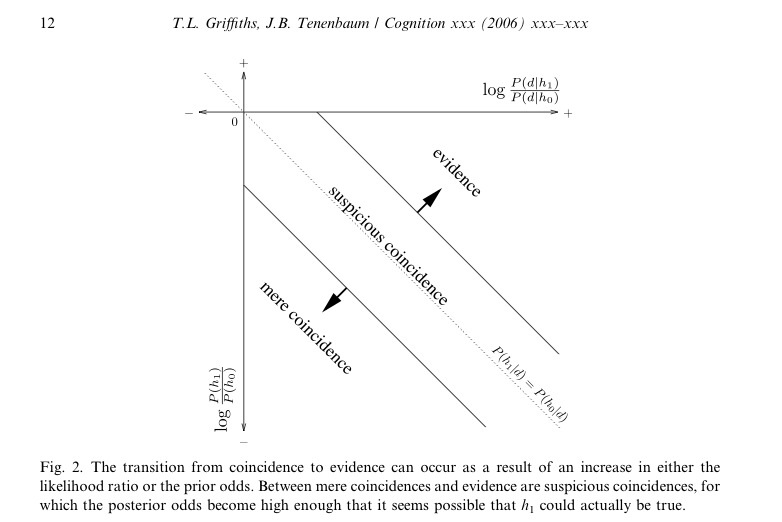

In "From mere coincidences to meaningful discoveries," Thomas Griffiths and Joshua Tenenbaum argue that while the perception of coincidence is often epistemic error, the same phenomenon underlies our ability to understand the world at all. Coincidences, they say, "are not just unlikely events, but rather events that are less likely under our currently favored theory of how the world works than under an alternative theory." They are an invitation to possibly change beliefs - the perception of a pattern in causal space whose existence had not been suspected before. A "mere coincidence" provides very weak evidence or supports a theory that is very unlikely according to evidence other than the coincidence. A new theory will not be adopted based on a "mere coincidence." A "suspicious coincidence," however, provides somewhat stronger evidence, or supports a more plausible hypothesis. The old, pre-existing theory and the new theory are rendered about equally likely by a "suspicious coincidence." And when a new theory is very plausible, or when the event supplies very strong evidence for it, it is not called a coincidence at all, but rather "evidence." The continuum is illustrated in a beautiful graphical and mathematical compression:

Griffiths and Tenenbaum go on to provide evidence that people are actually pretty good Bayesians when working on problems close to their experience. The brain naturally performs unconscious math, not with symbols but with a complicated array of emotions, neurotransmitters, and who knows what else. Hurley et al. say:

There are intrinsic statistics to our knowledge. When something is unlikely, we don't calculate the statistics - we simply know (or, rather, feel) that it is unlikely. The statistics have been precalculated for us, in our experience with the world such that our knowledge reflects the likelihood of events, and when these likelihoods are contradicted we are surprised.

[Inside Jokes, p. 242.]

Surprise is an essential feature of coincidence. Surprising phenomena are the most fertile grounds for adapting our models of the universe; surprise is even "believed to be a trigger for associative learning." An entity that cannot be surprised cannot learn, because its model of the universe is already so perfect that it cannot be improved.