Background

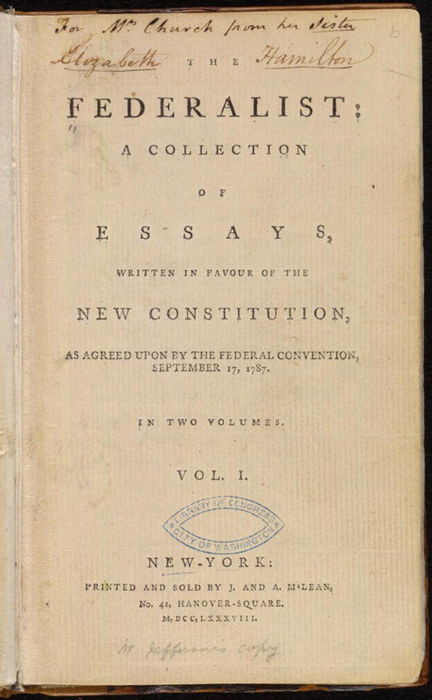

The Federalist Papers are a collection of 85 articles and essays written in the latter half of 1780 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the United States Constitution. Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written - the authorship at the time of publication was a closely guarded secret.

Following Hamilton's death in 1804, a list he wrote became public, which attributed a majority of the papers to himself, including some that seemed more likely the work of Madison (No. 49–58 and 62–63). The truth of who wrote the papers is still a little murky - there is general consensus on who wrote each paper, but unfortunately the truth has been lost to the annals of time.

A significant amount of prior research has been done on the Federalist Papers, including The Disputed Federalist Papers: SVM Feature Selection via Concave Minimization, Case Study: The Federalist Papers, and the seminal Inference in an Authorship Problem by Frederick Mosteller and David L. Wallace. These papers do the topic much more justice to the subject than I can in a blog post.

My goal is to recreate the results found by Mosteller and Wallace through modern statistical methods - namely K-Means clustering and TFIDF.

Data Gathering

The first step was to retrieve and clean the data. Luckily all the papers are in the public domain (and a piece of American History!), so they're hosted by the Gutenberg Library in a raw text document here.

I did some data processing to clean up all the collection into it's constituent papers:

import re

import string

papers = open("The-Federalist-Papers.txt")

lines = papers.read()

papers.close()

elem = re.split(r'FEDERALIST\.? No\.?', lines)

print(len(elem))

for i in range(len(elem)):

out = open("papers/" + str(i) + ".txt", "w")

out.write(elem[i])

out.close()I manually moved each paper into it's respective authors folder and cleaned up the Gutenberg header/footer. John Jay only wrote 4 papers (2, 3, 4, and 5), but then fell ill and contributed only one more essay, Federalist No. 64, to the series. For the purposes of this paper I discount him as having authored any of the disputed papers, as current historical consensus says that they were written by either Hamilton or Madison.

The disputed papers were papers 49 through 58 and 62 and 63, for a total of 12 of the 85. Now we could start training our model on the data.

Initial Attempts

This being my first foray into the world of unsupervised NLP, I wanted to get a good feel for prior work on author attribution. I read a lot of papers, articles, and blog posts to get an intuition on how to get started. I put some of my favorites in the Resources and Prior Work section below. Note that because we have a (semi) ground truth, supervised learning would be a better approach - however, this was a learning exercise, and I wanted to see if I could replicate the results in an unsupervised manner.

I decided to go with 3 features - lexical similarity in sentence structure, lexical similarity in punctuation, and syntactic similarity.

I imported all the definitive Madison and Hamilton papers and created my original K-Means fit.

K-Means Clustering

K-means clustering aims to partition n observations into k clusters in which each observation belongs to the cluster with the nearest mean, serving as a prototype of the cluster. This results in a partitioning of the data space into Voronoi cells. For our example we'll have 68 observations (papers) into 2 clusters (2 authors, Madison and Hamilton).

Once the data has been converted into workable features, we can fit them onto a 2-cluster model. This is unsupervised - we are effectively just pouring in our (ideally) significant data and telling it that there are two distinct sets within it, and to try and extricate them.

Feature Sets

Feature sets are what we'll use as indicators - we need to transform our text into machine-workable data based on criteria we select.

Lexical Similarity

We first tokenize each paper with tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(single_paper_text.lower()) - this gives us an array of lowercase words with adjoined punctuation. Then we extract just the words with words = word_tokenizer.tokenize(single_paper_text.lower()).

Our goal is two-fold - the first is to get a straightforward measure of the average number of words per sentence, and the second is to somehow score the lexical diversity of the paper.

We can arrive to a rough estimate of the lexical diversity by taking the vocabulary (number of unique words) divided by the total number of words. As an example, take the following snippet:

"The man went to the other man's house"

First we'd tokenize it to ["The", "man", "went", "to", "the", "other", "man's", "house"] and then split it into just words - ["the", "man", "went", "to", "the", "other", "man", "house"].

The number of unique words is 7, while the total number of words would be 8. The lexical diversity score would be 7/8 (0.875). As you can see this is a crude measure of lexical diversity - ideally, a more advanced model would also take into account word rarity and length. However, on a large enough training set in which our two authors have comparable speech patterns it should be enough to distinguish them.

Lexical Similarity - Punctuation

This feature is also fairly straightforward - we count the average number of times they use a semicolon, a colon, and a dash in their writing.

Syntactic Similarity

NLTK has a function for part of speech labeling, and our feature vector is comprised of frequencies for the most common part of speech tags - 'NN', 'NNP', 'DT', 'IN', 'JJ', and 'NNS' (full explanation of what each of these means is here).

We're effectively looking for patterns in their habits of speech - whether they often say "Noun comma noun" or "adverb verb comma noun", etc.

Putting it all together

Once we've defined the feature generators, we can put it all together.

We generate an array and large string with all known papers.

hamilton_papers = []

for fn in hamilton:

with open(fn) as f:

hamilton_papers.append(f.read().replace('\n', ' ').replace('\r',''))

hamilton_papers_all = ' '.join(hamilton_papers)

madison_papers = []

for fn in madison:

with open(fn) as f:

madison_papers.append(f.read().replace('\n', ' ').replace('\r',''))

madison_papers_all = ' '.join(madison_papers)

disputed_papers = []

disputed_papers_file_names = []

for fn in disputed:

with open(fn) as f:

disputed_papers.append(f.read().replace('\n', ' ').replace('\r',''))

disputed_papers_file_names.append(ntpath.basename(fn))

disputed_papers_all = ' '.join(disputed_papers)

known_papers_all = hamilton_papers_all + " " + madison_papers_all

known_papers = hamilton_papers + madison_papersNext we generate the feature sets for the known papers:

known_set = list(LexicalFeatures(known_papers, known_papers_all))

known_set.append(SyntacticFeatures(known_papers, known_papers_all))

classifications = [PredictAuthors(fvs) for fvs in known_set]As well as the feature set for the unknown:

# Get FVS/normalized data to predict from disputed papers

disputed_set = list(LexicalFeatures(disputed_papers, disputed_papers_all))

disputed_set.append(SyntacticFeatures(disputed_papers, disputed_papers_all))Finally, we predict the authorship for each of the disputed papers:

results = list()

results.append([classifications[0].predict(disputed_set[0]),"Lexical Features"]) # Predict results of Lexical Features

results.append([classifications[1].predict(disputed_set[1]),"Lexical Features - Punctuation"]) # Predict results of Lexical Features, Punctuation

results.append([classifications[2].predict(disputed_set[2]),"Syntactic Features"]) # Predict results of their syntactic featureResults

| 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 62 | 63 |

|---|

| Lexical Features | H | H | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | H | M |

| Lexical Features - Punctuation | H | H | M | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | M | M |

| Syntactic Features | M | M | M | M | M | H | M | M | M | M | M | M |

| Final Results | H | H | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M |

The models predict that 10 of the 12 papers were written by Madison.

The results mirror those found in the 1960s Mosteller and Wallace. There does seem to be some disagreement on a few papers, and our classifier labels papers 49 and 50 as Hamilton's, but overall the results seem fairly accurate!

Conclusion

All the code in this article (as well as the dataset) can be found here. The feature sets seem fairly good - the only one that I believe isn't up to par is the Lexical Features - Punctuation. It feels too rudimentary and naive right now- I'll probably take a stab at improving it some point in the future.

Overall this was a fun introduction to statistical methods and k-means clustering.

If it looks like I did anything obviously wrong or have the wrong intuition about anything, please don't hesitate to reach out!

Update 7/25/18

Jon Miller, from the University of Akron, replied with the following:

[Your blog post] led to a quick question: what evidence do we have that these men did their own punctuation? It's my understanding that until about the Civil War most publications were submitted as handwritten documents. Someone in the printer's office then did the manual labor of adding the "points." In the decades before the Civil War there was popular demand for books that described general rules--Edgar A. Poe wrote that no such book existed. And the ones that appear to have been the most popular were popular with typesetters. Plus there are a lot of jokes and warnings in newspaper editorial columns to the effect of "if we cannot read your handwriting, do not complain if we guess incorrectly." There are exceptions and these papers are so important, it may well be the case that H and M reviewed printed proofs for the book edition and corrected the points. But the default, I would imagine, would have been that they let some dirty typo do that work. And so if two or more people did the pages, there might be two or three styles. And they did not set up pages sequentially -- one man might have done 4, 16, 28, and 40 while another did 5, 17, 29, and 41. They would count words and draw lines in the manuscript to determine which sections would fall on which pages in the final product.

This is an interesting problem - it's entirely possible that the punctuation feature is inaccurate, and that the punctuation added in each paper was done by different copy editors or someone in the printers office.

I invite any one who is a Madison or Hamilton historian to reach out if you know anything about this.