As a W2'd employee you don't have a lot of strategies you can use to minimize your taxes at the end of the year. You can be making $1,000,000 a year, but if most or all of that income comes from a direct employer and shows up on your W2, your tax bill at the end of the year is effectively a simple formula with very little wiggle room.

If you don't have any forms of business or otherwise more complex revenue, your opportunities to offset income are fairly limited. If you participate in the equity markets (or any other form of fairly liquid market that leads to capital gains and losses), however, you open yourself up to strategies that can help minimize your tax liability. One of the most straightforward ones is called tax loss harvesting.

What is tax loss harvesting?

TL;DR

Tax loss harvesting is using realized losses to offset capital gains, while using those realized losses to purchase broadly similar securities. If you hold an asset that is worth less than you bought it for, you sell, take the loss, and purchase a similar (but not too similar) asset. You take the losses, and use them to offset income for that year, while any gains on the new similar security are unrealized.

You cannot tax loss harvest if you have no assets that have lost value (as in, they are worth less now than when you purchased them).

Basics

The core principle behind tax loss harvesting is that of realized versus unrealized losses and gains. If you buy and hold a security, you don't report its change in value until the year that you sell it. It's important to understand this.

If this year (2021) you buy a share of Company A, worth $100, and at the end of the year it's worth $120, you don't have to report $20 in income, as this is an unrealized gain. If you decide to sell it next year (2022), you'll owe capital gains1.

If instead the share of Company A is worth $90 at the end of the year, you have a $10 unrealized loss. This is always based on the price you paid for the asset - if the price of the security you paid $100 for is $120 in November, but drops to $90 in December, you don't have $30 in losses.

If you were to sell that security, you have effectively lost $10 - you paid $100 and only got back $90. This is not ideal, but this is the risk you take in participating in the public markets2. You can now take this $10 loss and offset any other capital gains you made this year.

Wash sale

You cannot immediately repurchase the same security due to the wash sale rule - if you repurchase it within 30 days, any losses or gains can't be reported. IRS section 1091 states that your tax loss will be disallowed if you buy the same security, an option to buy the security, or a substantially identical security, within 30 days of when you sold the security.

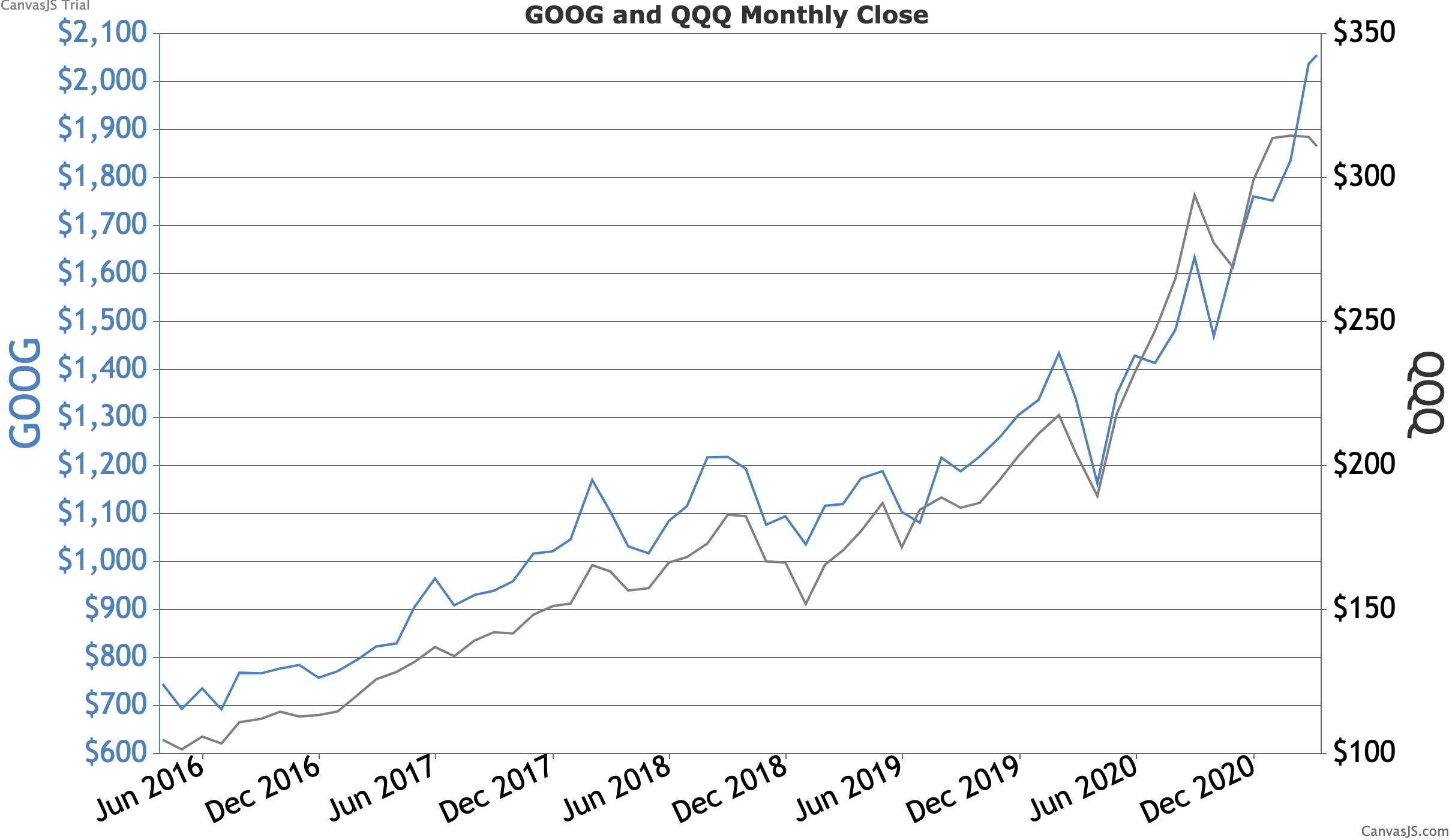

"Substantially identical" is a broad, non specific statement, however, which allows you to invest in securities that are correlated but not "substantially identical" - i.e. if you sell GOOG and buy QQQ.

Tax loss harvesting does open you up to changes in your risk exposure - while two assets or securities might be historically correlated, there is no guarantee that they'll continue behaving in the same way. If you truly believe in Google, it's possible that it'll outperform whatever security you pick to replace it, and you'll be leaving potential capital gains on the table and underperform your beliefs.

Why sell the asset?

Let's take a slightly more realistic example. You have $100,000 and are deciding what to do with it. There are many different approaches you can take, but let's say that you decide to invest in two areas - $50,000 in an ETF that tracks tech stocks, and $50,000 in an ETF that tracks healthcare stocks.

You've bought:

- $50,000 of IYH

- $50,000 of IYW

A month passes, and your new portfolio looks like this:

- $48,000 of IYH

- $53,000 of IYW

Your cost basis is still $100,000, while your portfolio is worth $101,000; it has $1,000 of unrealized gains. However, within your portfolio, you have one asset (IYH) that has an unrealized loss of $2,000 and one asset (IYW) with an unrealized gain of $3,000.

If it was the case that no asset has lost value, you could not tax loss harvest. This is the optimal case, but is not realistic. Nearly every diversified portfolio is going to have winners and losers.

You can never go back in time. If you'd known then what you know now, you would go all in on IYW (or, more lucratively, have gone out and bought a lottery ticket with the winning numbers). This isn't possible though. Your portfolio value is your portfolio value, and there's no changing that fact. At this point you either still believe in the assets, and want that level of diversification, or you don't and should change up your portfolio.

Your assets can generally do one of three things - they can go up, they can go down, or they can stay roughly the same price.

There are six cases - the three above, for when you hold and when you tax loss harvest (TLH):

| IYH goes up | IYH goes down | IYH stays the same |

|---|

| TLH | On selling IYH, you took a realized loss. If the security you chose to replace IYH is similarly correlated, you would make unrealized gain on the increase in value of that new security. | On selling IYH, you took a realized loss. This offsets other capital gains (or ordinary income) for the year. If the security you chose to replace IYH with is correlated, it will also have lost value. You can proceed to tax loss harvest again. | On selling IYH, you took a realized loss. This offsets other capital gains (or ordinary income) for the year. If the security you chose to replace IYH with is correlated, it will remain roughly the same, and your overall portfolio value is the same. |

| Hold | Your unrealized losses diminish, and perhaps become an unrealized gain. Your tax liability for the year remains unchanged | Your unrealized losses increase. Your tax liability for the year remains unchanged. | Your unrealized losses remain the same. Your tax liability for the year remains unchanged |

If you don't believe that IYH is a good place to store your money, then you should sell it no matter what. If you believe that IYH is going to go down more in the future, you should sell it and purchase an asset in another sector, or short IYH.

If you still believe that IYH is a good bet, though, you can get some benefit of the loss, while still being exposed to the underlying sector it tracks or is a part of. Tax loss harvesting is a way to keep a relatively similar portfolio structure, exposure and risk tolerance, while reaping the benefits of daily volatility and potential losses.

Example

In the below example, you make $10,000 a year, have an existing $15,000 portfolio that you recently invested in the market, and a 30% flat tax rate. It shows that tax loss harvesting will provide you with a significantly reduced tax liability.

Common misconceptions

You can only take $3,000 of losses per year

You can only offset $3,000 of ordinary income with losses per year. However, you can always offset any capital gains with historical losses, until you've broken even.

If you lost $100,000 last year, and this year you made $50,000 of W2 income (not capital gains or from investments), you can take $3,000 out of the $100,000 loss to offset the ordinary income.

Your taxable income will be $47,000, and your current lifetime losses is $97,000.

If next year you make $100,000 from capital gains and investments (not from your job or ordinary income), the $97,000 can be used to offset that. You'll only owe taxes on $3,000, and your historical losses have been wiped out.

Effectively, capital losses can offset capital gains at any point in the future, with no limit. They can only offset other income by a maximum of $3,000 per year.

A small caveat here is that you must offset gains with the same type of losses first - short term to short term and long term to long term. Only once you've exhausted one of the buckets can you apply the losses to the other one.

Tax loss harvesting is illegal

At its core tax loss harvesting is simply buying and selling assets, then reporting those losses. You've already lost money on those assets - you are never ahead tax loss harvesting than if those assets had actually made you money. There are many arguments around whether capital gains should be taxed as regular income or not, and whether the current system should be changed, but those are broader political questions.

You can immediately repurchase the same security

If you repurchase the security you sold for a loss within 30 days, you are disallowed to claim that loss on your taxes.

Conclusion

If you want a much more thorough explanation of how the wash sale rule and tax loss harvesting works for stocks, bonds and mutual funds, I recommend reading this article from etf.com.

If employed properly, tax loss harvesting can save thousands on your year end tax bill. If you're doing this manually you can probably reap most of the benefits by doing this quarterly or even yearly. Many of the automated robo-advisors do this for you already (Wealthfront, Schwab Intelligent Portfolios, etc) automatically - in fact, they can do it daily.

It's always important to know what tools you have in your arsenal to maintain a healthy financial profile, and tax loss harvesting is one of the first leves you get access to once you leave the relatively simple world of W2 income.

Footnotes

-

Either short term if it has been less than 12 months since purchase, which is your regular tax rate, or long term if its been more than a year since purchase, which ranges from 0% to 20% https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/taxes/capital-gains-tax-rates ↩

-

What is the ideal case? The ideal case is that every investment you ever make never loses any money from its principal. The value is never worth less than what you paid for it. In this case you cannot employ tax loss harvesting - as the name implies, you are harvesting the losses from the security. ↩