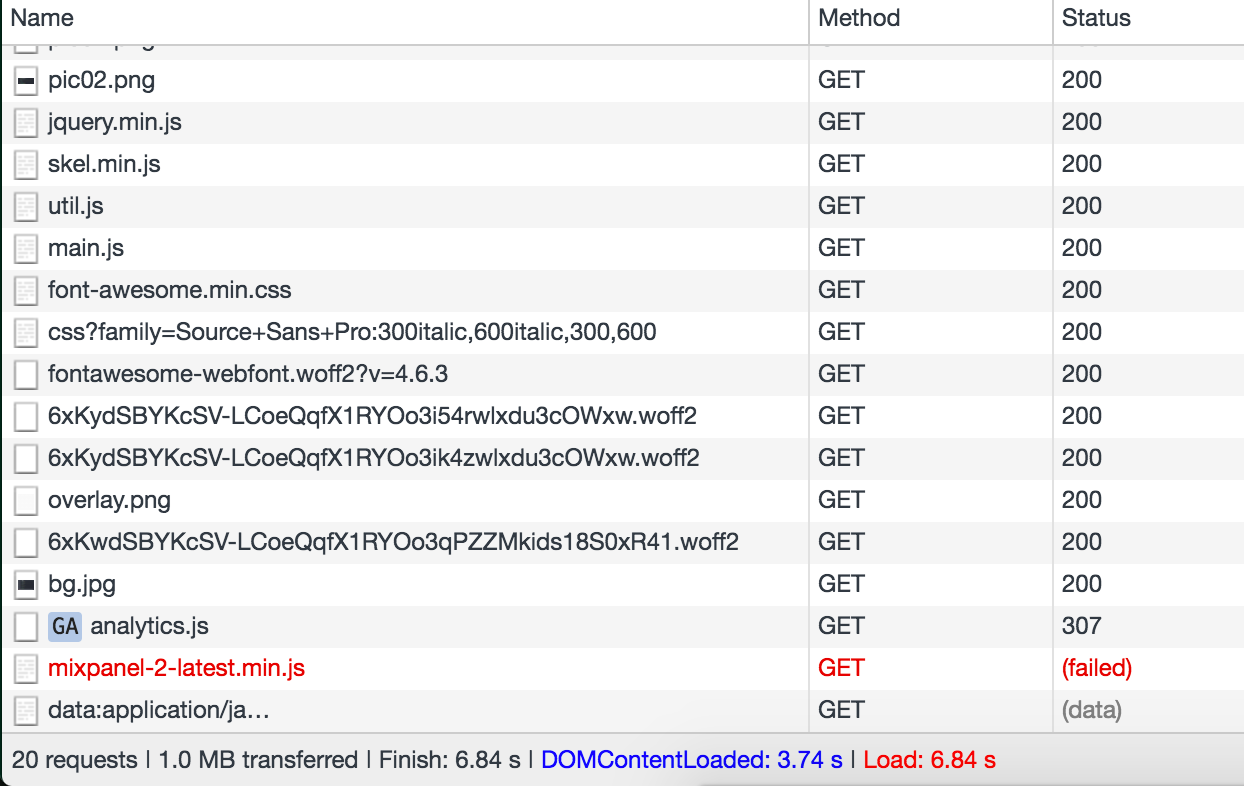

A couple months ago, I was traveling outside of the U.S. and wanted to show a friend a link on my personal (static) site. I tried navigating to my website, but it took much longer than I anticipated. There’s absolutely nothing dynamic about it — it has animations and some responsive design, but the content always stays the same. I was pretty appalled at the results, ~4s to DOMContentLoaded, and 6.8s for a full page load. There were 20 requests for a static site, with 1mb of total data transferred. I was accustomed to my 1Gb/s, low latency internet in Los Angeles connecting to my server in San Francisco, which made this monstrosity seem lightning fast. In Italy, at 8mb/s, it was a different picture entirely.

This was my first foray into optimizations. Up to this point, any time I wanted to add a library or resource, I would just throw it in and point to it with src="...". I had paid zero attention to any form of performance, from caching to inlining to lazy loading.

I started looking around for people with similar experiences. Unfortunately, a lot of the literature on static optimizations gets dated fairly quickly — recommendations from 2010 or 2011 discussed libraries or made assumptions that simply weren’t true anymore, or just repeated the same maxims over and over.

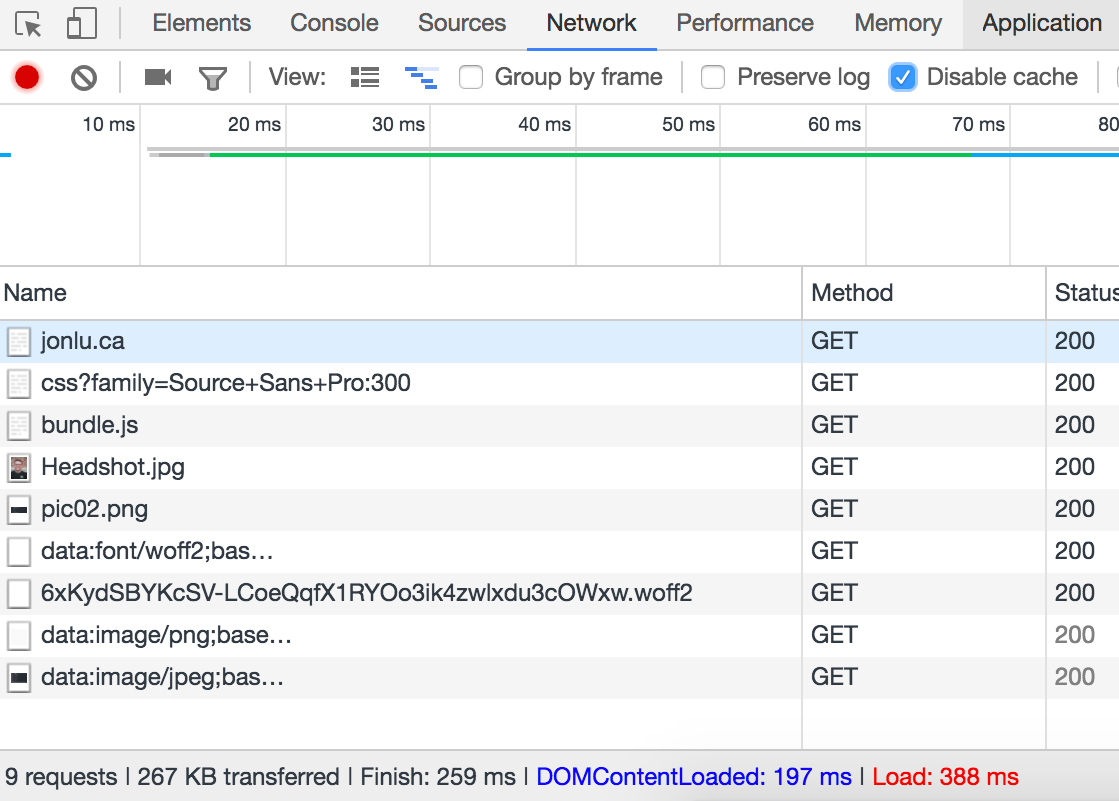

However, I did find two great sources of information — High Performance Browser Networking and Dan Luu’s similar experience with optimizing static sites. While I didn’t go as far as Dan in stripping formatting and content, I did manage to get my page load to be roughly 10x faster, to about a fifth of a second for DOMContentLoaded and only 388ms for full page load (which is actually a little inaccurate, as it tacks on the lazy loading explained below).

The Process

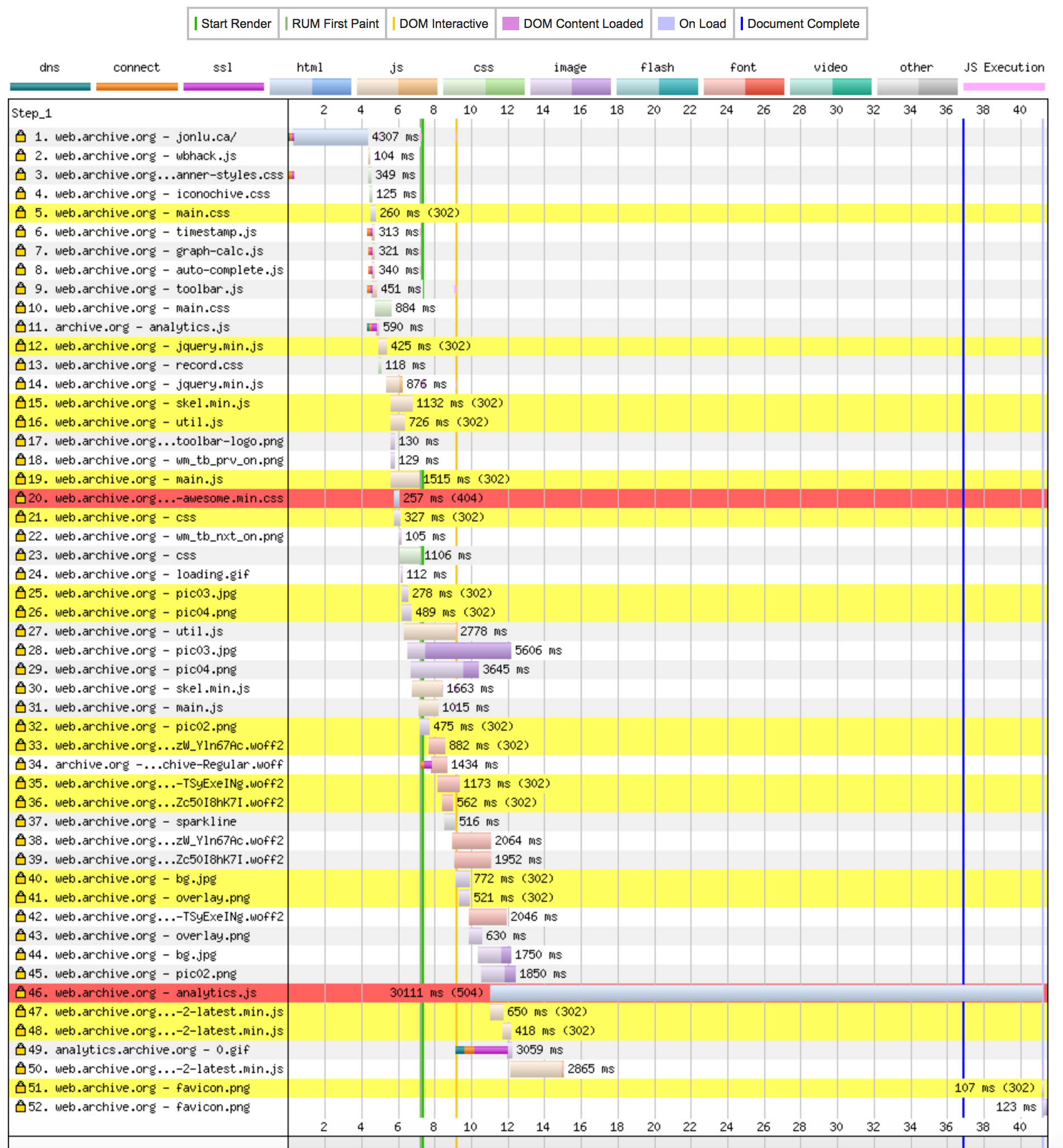

The first step of the process was to profile the site. I wanted to figure out what was taking the longest, and how to best parallelize everything. I ran various tools to profile my site and test it from various locations around the world, including:

Some of these offered suggestions on improvements, but there’s only so much you can do when your static site has 50 requests — everything from a spacer gif left as a remnant from the 90s to assets that aren’t used (I was loading 6 fonts and only using 1).

Timeline for my site — I tested this on the Web Archive as I didn’t screenshot the original one, but it looks similar enough to what I saw a few months ago.

Timeline for my site — I tested this on the Web Archive as I didn’t screenshot the original one, but it looks similar enough to what I saw a few months ago.

I wanted to improve everything that I had control over — from the contents and speed of the javascript to the actual web server (Nginx) and DNS settings.

Optimizations

Minify and Coalesce Resources

The first thing I noticed was that I was making a dozen requests each for CSS and JS (without any form of HTTP keepalive), and to various sites, some of which were https. This added multiple round trips to various CDNs or servers, and some JS files were requesting others, which caused the blocking cascade seen above.

I used webpack to coalesce all my resources into a single js file. Any time I make a change to my content, it automatically minifies and turns all my dependencies into a single file.

I played around with different options — currently, this single bundle.js file is in the <head> of my site, and is blocking. It’s final size is 829kb, and that includes every single non-image asset (fonts, css, all libraries and dependencies, and js). The vast majority of this is are the font-awesome fonts, which make up 724 of the 829kb.

I went through the Font Awesome library and stripped all but the three icons I was using — fa-github, fa-envelope, and fa-code. I used a service called fontello to only pull the icons I needed. The new size was just 94kb.

The way the site is currently built, it won’t look correct if we only have stylesheets, so I accepted the blocking nature of a single bundle.js. Load times are ~118ms, which is more than an order of magnitude better than above.

This also had a few added benefits — I was no longer pointing to 3rd party resources or CDNs, so the user would not need to 1) perform a DNS query to that resource, 2) Perform the https handshake, and 3) actually wait for the full download from that resource.

While CDNs and distributed caching might make sense for large scale, distributed sites, it does not make sense for my small static site. The additional hundred milliseconds or so are a worthwhile tradeoff.

Compress Resources

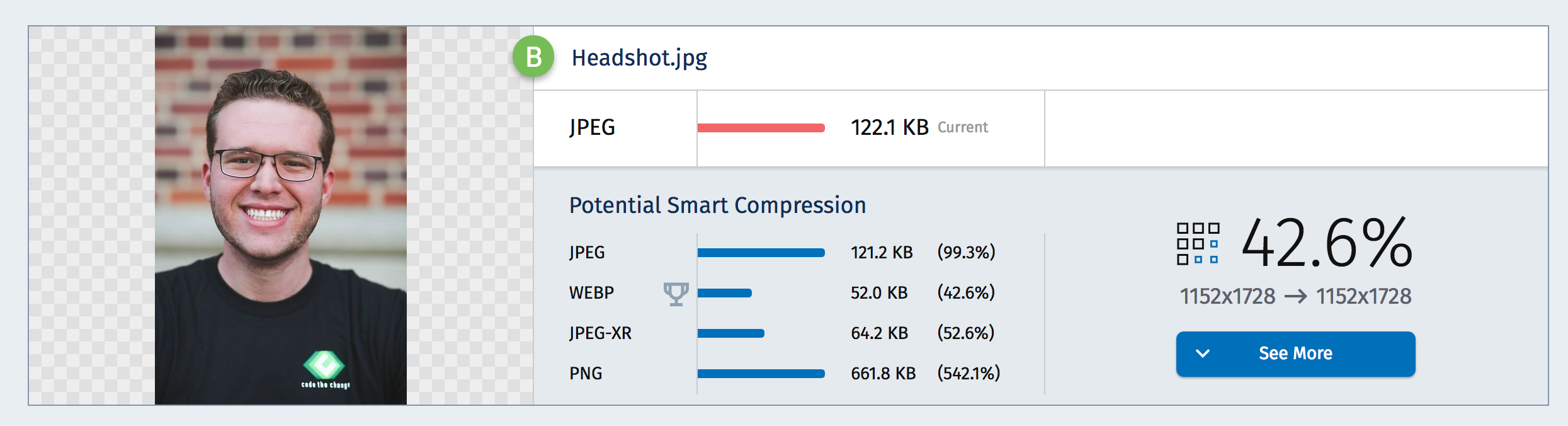

I was loading an 8mb sized headshot and then displaying it at 10% width/height. This wasn’t just a lack of optimization — this was almost negligent usage of users bandwidth.

I compressed all my images using https://webspeedtest.cloudinary.com/ — it also suggested I switch to webp, but I wanted to remain as compatible with as many browsers as possible, so I stuck to jpg. It’s possible to set up a system in which webp only gets delivered to browsers that support it, but I wanted to remain as simple as possible, and the benefits for that added layer of abstraction did not seem worth it.

Improve Web Server — HTTP2, TLS, and More

The first thing I did was transition to https — when I started, I was running Nginx bare on port 80, just serving files from /var/www/html

I started by setting up https and redirecting all http requests to https. I got my TLS certificate from Let’s Encrypt (an great organization that just started signing wildcard certificates as well!).

Just by adding the http2 directive, Nginx was able to take advantage of all the modern, baked in advantages of the newest HTTP features. Note that if you want to take advantage of HTTP2 (previously SPDY), you must use HTTPS. Read more about it here.

You can also take advantage of HTTP2 push directives with* http2_push images/Headshot.jpg;*

Note: Enabling gzip and TLS might put you at risk for BREACH. As this is a static site, and the actual risks for BREACH are fairy low, I felt comfortable keeping compression on.

Utilize Caching & Compression Directives

What more could be accomplished through just Nginx? The first things that jump out are caching and compression directives.

I was sending raw, uncompressed HTML. With just a single gzip on; line, I was able to go from 16000 bytes to 8000 bytes, a decrease of 50%.

We are actually able to improve this number even further — if set Nginx’s gzip_static on, it’ll look for precompressed versions of all requested files before hand. This goes hand in hand with our webpack config above — we can use the ZopflicPlugin to precompress all our files, at build time! This saves computational resources, and allows us to maximize our compression with no tradeoff to speed.

Additionally, my site changes fairly infrequently, so I wanted the resources to be cached for as long as possible. This would make it so that, on subsequent visits, users would not need to redownload all assets (especially bundle.js).

My updated server config looks like this. Note that I won’t touch on all the changes I made, such as TCP settings changes, gzip directives, and file cache. If you’d like to know more about these, read this article on tuning Nginx.

And the corresponding server block

Lazy Loading

Lastly there was a small change to my actual site that would improve things by a non-negligible amount. There are 5 images that aren’t seen until you press on their corresponding tabs, but that were loaded at the same time as everything else (due to their being in a img src="" tag.

I wrote a short script to modify the attribute with every element with the lazyload class. These images would only be loaded once the corresponding box was clicked.

So once the document had completed loading, it would modify the <img> tags so that they went from <img data-src="..."> to <img src="...">, and load it in the background.

Future Improvements

There are a few other changes that could improve the page load speeds — most notably, using Service Workers to cache and intercept all requests, and have the site operate even offline, and caching content on CDNs so that users do not need to do a full round trip to the server in SF. These are worthwhile changes, but not particularly important for a personal static site that serves as an online resume/about me page.

Conclusion

This improved my page load times from more than 8 seconds to ~350ms on first page load, and an insane ~200ms on subsequent ones. I really recommend reading through all of High Performance Browser Networking — it’s a fairly quick read, and provides an incredibly well written overview of the modern internet, and optimizing at every layer of the modern internet model.

Did I miss anything? See anything that violates best practices or that could improve my performance even more? Feel free to reach out — JonLuca De Caro!