I was recently in a discussion about the propagation of information, and how our intuitions about the general level of exposure of things we might take for granted within society is wrong. I wanted to wrap my head around a few key notions of our perception of the world and it's changes in the last 3 decades.

Exponentiation

Understanding economies of scale does not come naturally for humans. It's often hard to think of the actual differences between more than a few orders of magnitude. You can, of course, do the math, but it's hard to have intuition about the size of exponentiation.

Let's use a few examples to wrap our heads around this. The now-famous video Powers of 10, published in 1977, is a good way to start.

The difference in orders of magnitude between the radius of an electron and the size of the known universe is 44 ($$ 10^-18 $$ and $$ 10^26 $$ respectively)

Size is a great introduction because it's easy to visualize. Things get a bit difficult when you think about abstract things like time.

$$ 10^3 $$ (1 Thousand) seconds is 16 minutes. $$ 10^6 $$ (1 Million) seconds is 11 days. $$ 10^9 $$ (1 Billion) seconds is 31 years.The topic becomes especially unintuitive when we get to information. What does it mean, from a sociological perspective, for a viral video to have been seen 10,000 times? What's the difference between 10,000 and 100,000? How can we model this, and what it means for an order of magnitude (or a couple!) more people to have access to information?

This blog post will primarily focus on modeling the propagation of information through society, and how there have been a few key revolutions that have changed the way we treat information.

It's fairly easy to understand what it means for something to go locally viral - say, a rumor in a high school. It's also pretty straightforward to understand what it means for something to go as "viral" as possible, like news of the new President of the United States after an election. But the differences in the propagation between these two extremes is massive, and there is no single algorithm that works at all scales. A great paper on Simple Graph Models was published in 2015 regarding this exact problem.

Information

Information can be viewed as arbitrary data such as ideologies, facts, and discoveries, as flow through a directed graph.

Each node can represent any arbitrary container of information - from a sociological view, the smallest scale would be each node being a person, and each edge being the transfer of that information from one person to another. A larger interpretation would be each node being a civilization and time period, and each edge represents the collective information shared by that collection of humans being passed on to the next. Of course, in this larger interpretation it would look much more like a tree than a random graph, but the point still stands.

The above would be a pretty good approximation for a small group of friends. People talk between each other quite a bit, and have a pretty consistent group of people they normally interact with. A few of these people bridge the gap between friend groups, and can introduce ideas to each other.

This view helps show how the information spreads, but it does a poor job of illustrating the scale and speed. It's only with an added dimension, time, that this becomes an accurate representation of information and virality.

Using this model we can see the the scales and periods of information growth. All arbitrary information will have an end point, a time in which that information can be considered lost, dead, or waiting for rediscovery. Up until recently, information used to be an extremely fragile system - it was usually clustered around the same few nodes (social groups), with it rarely escaping. You'd get the occasional jump from one cluster to the other, which would quickly infect the cluster, but it would again wait a while. The graph above was explicitly designed to be connected, so it's only an accurate model for relatively recent times.

Our modern informational framework has data persist significantly longer - so much so that an adage has come out, "nothing is ever deleted on the internet". We have the privilege of treating information as a commodity, which is an extremely recent development.

Information as Memory

The generational transfer of information used to be much less formalized and absolute. The above graphs were rarely truths - in reality, societal circles were much more disjoint, with information needing to be rediscovered over and over again before it was permanently ingrained in the public societal "memory".

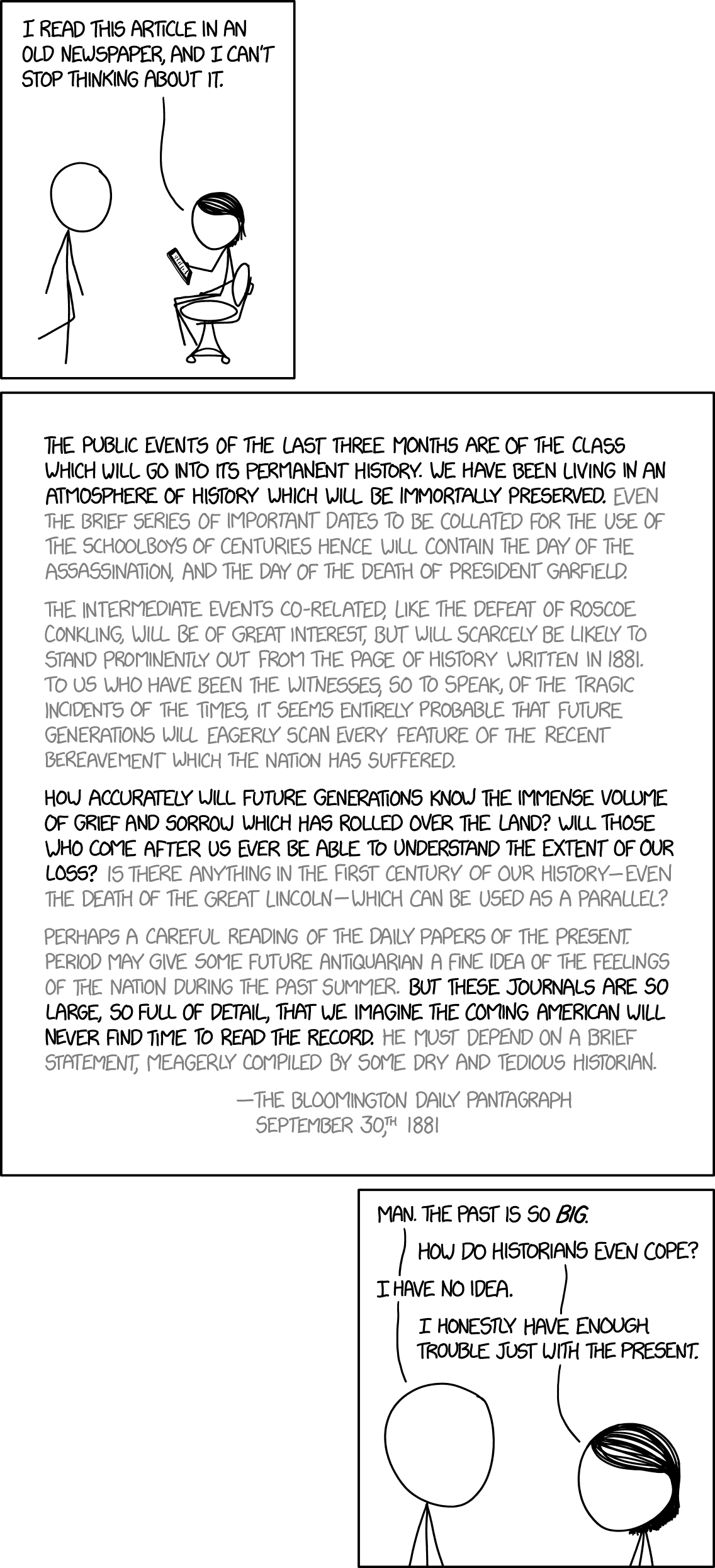

Information, specifically our current information about history, is our societal memory. The vast majority of human history and events has been lost - facts have been mangled, the actual reasons and motivations behind pivotal events lost to the sands of time.

It's the most enduring version of survivorship bias - we treat history as this concrete, tree of events, when in reality it has been pruned, over and over, such that what is left, or what we consider to be ancient history, is but a shadow of reality.

The Information Age

The models above don't make any implications on their own, but they do highlight an interesting trend. Within the last 3 decades, the propagation of information has lost a lot of the physical boundaries it used to have. Societal memory becomes permanent - what used to be stored in physical books or passed down through oral tradition becomes ingrained in data centers and the internet. Absolute physical distance is rendered meaningless with the advent of modern communication protocols. Censorship on a grand scale becomes nigh on impossible, so government prohibition only works in the most extreme of cases. Language and translation is getting better every day, with just this year Google Translate averaging better BLEU scores than UN translators on certain languages. The biggest difference, however, is the persistence and storage of information. There is more recorded history of the past 30 decades than in the 2000 that preceded it. Every picture, every document, every agreement is saved and copied dozens of times. In 2018, we estimate that global internet traffic will nearly triple in the next 5 years, from 1.2ZB in 2016 to 3.3ZB in 2021.